“The interesting irony of formal attire is that almost without exception, every aspect of the masculine evening costume derives from the sport of horseback riding.”

G. Bruce Boyer – Author Elegance: A Quality Guide to Menswear

Georgian Fashion Revolution: Origins of Modern Evening Attire

The tradition of dressing up after dark has existed for centuries. Perhaps the most obvious evidence of this is the “dress circle” section in theaters, a term derived from the eighteenth and nineteenth-century grand European opera houses which restricted this exclusive seating area to patrons who were properly attired. However, the philosophy of dress clothes underwent a dramatic change at the turn of the nineteenth century when modern evening wear evolved from surprisingly rustic origins.

Early 1700s – Men Dress Like Peacocks

Prior to the mid-1700s men’s fashion in Europe was largely a peacock affair for aristocrats who adorned themselves in the most extravagant clothing they could concoct. Ironically, Pitti Uomo today showcases men who fully embrace that peacock spirit.

The standard wardrobe of the time consisted of cutaway coats with long, stiff skirts combined with elongated waistcoats that were elaborately embroidered and knee-length breeches worn with stockings and buckled shoes. For ordinary occasions, this apparel would be made of cloth of various kinds but for formal affairs, there was no substitute for imported silks and satins often embellished with gold trim.

Fashions Are Dictated By The Elite

As it had been since the advent of civilization, fashions were dictated by the elite and followed by the masses. The social pecking order was maintained via dress; not only by the expense of the fabrics but also by the impracticality of the fashions. Garments of the upper classes were deliberately uncomfortable and close-fitting so as to render them unfit for the manual labors of the lower ranks.

Mid-1700s – The Aristocracy Moves Toward Comfort

The English would revolutionize fashion history when their aristocracy developed a preference for the more comfortable garments of the working man. It began in the 1730s with the adoption of the common frock, a simpler and looser-fitting coat that was more practical for hunting and riding, pastimes which were quickly gaining favor among the elite.

King George III was a particular aficionado of outdoor activities so his ascension to the throne in 1760 ensured widespread acceptance of the new concept of the “country gentleman”. Toward the end of the 18th century, this new look emigrated from country to town where it was perfected by a man whose profound influence on male fashion has lasted to this day: George “Beau” Brummell.

Beau Brummell and Regency Fashion: The Father of the Modern Evening Ensemble

Beau Brummell was a middle-class Englishman with social ambitions well beyond his income. By the time he gained his inheritance and moved to London in 1799 he had managed to infiltrate the highest level of society and developed a close friendship with the Prince of Wales, the future George IV.

However, it was financially impossible, not to mention socially unacceptable, for a man of Brummell’s station to mimic the opulent garb of the upper class. Thus he set out to perfect the more affordable look of the country gentleman by combining his impeccable sartorial tastes with an impressive physique for displaying them.

From Drab Country Attire To Popular Fashion

Brummell’s artful strategy was to elevate the common drabness of country attire to a refined minimalism. He replaced the bright colors previously favored by the elite with a limited palette of dark coats and plain, light-colored waistcoats and pantaloons. Patterned waistcoats were traded in for monochrome versions, frilled shirts were replaced by plain styles and lace cravats were superseded by starched linen neckcloths.

Military & Equestrian Flair Help To Cement Brummel’s Role As Arbiter Elegantiarum

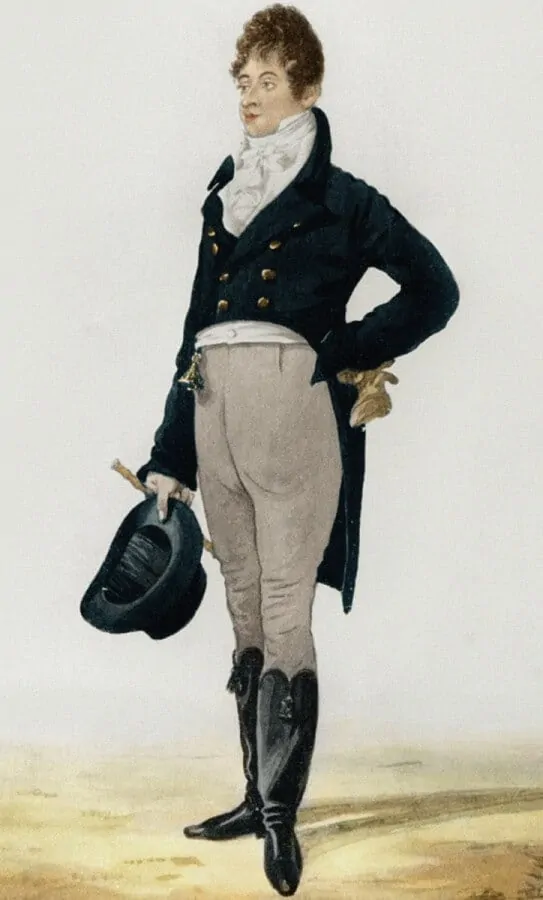

Brummell also imported an understated military and equestrian flair to his wardrobe to emphasize the wearer’s physique and authority. This was done primarily by adopting the tailcoat – a frock coat with a skirt cut away at the front for easier wear when riding – as his coat of choice and enhancing it with skillful tailoring to suggest broad shoulders and a trim waist. Below this, his muscular legs were emphasized by the wearing of light-colored pantaloons – tight-fitting ankle-length trousers held in place by a strap under the foot – which disappeared into knee-high black leather riding boots styled after those of the Prussian military.

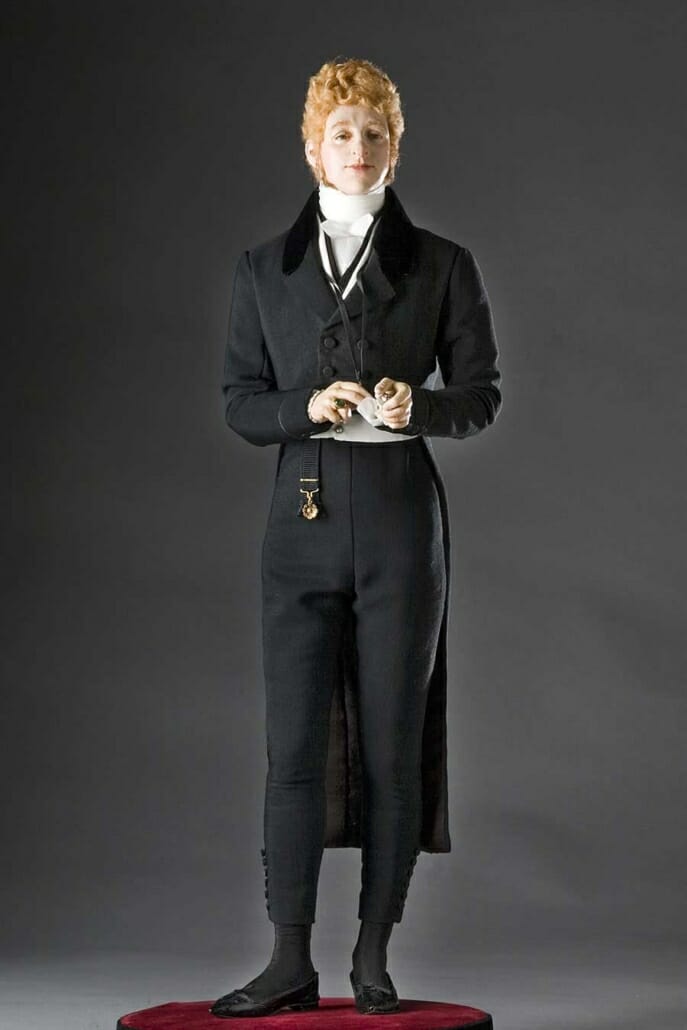

The end result of these innovations was an ensemble vastly more regal than the ill-fitting apparel of the country squires and sans-culottes that originally inspired it. It was subsequently adopted by the haute monde as the meticulous Regency wardrobe seen so often in Jane Austen film adaptations. But redefining traditional day wear was only half the equation in a society which reserved their most elite functions, and their most formal attire, until after dark.

Regency Evening Dress: Etiquette

The politics of dress in the early eighteenth century was a serious matter. Knowing what to wear and when to wear it was an essential life skill for the upper class and part of an elaborate etiquette used to distinguish the purebred gentry from the merely rich. The underlying principle was summarized by a period etiquette guide which explained that one’s attire should be adapted to the occasion, season, place and time so that there was “harmony between the stiffness of the coat and of the company.”

***ADD IMAGE: English Evening Full Dress, 1807***

Undress, Half Dress, & Full Dress

Depending on the authority cited, this aesthetic harmony was governed by classifying clothing as Undress and Dress, or the slightly more defined hierarchy of Undress, Half Dress and Full Dress. Within these categories was a secondary ranking of the many ensembles that might be worn by the gentry over the course of a day. Generally speaking, the appropriateness of clothing was based on the following principles:

- Informal clothing worn in the privacy of one’s home was at the bottom of the sartorial ladder because public appearances necessitated dressier standards

- Attire for outdoor leisure activities was next in rank but inferior to the professional apparel required for affairs in the city (thus the popular differentiation between “town and country”)

- Aristocratic socializing called for more upscale dress than did mingling with the general populace

- The formality of evening affairs trumped all other dress factors

Evening Dress

Most of these formal distinctions are inherently logical and remain relevant in society today. But the nineteenth-century practice of dressing like an orchestra conductor every evening bears some explanation. A good place to start is the origin of dressing for dinner as provided by Nicholas Antongiavanni quoting fellow menswear historian Hardy Amies:

“Men spent a great part of the day on horseback. Personal hygiene apart, you did not want to bring the smell of the stables into the house.” And the clothes that men changed into were more formal than the ones they changed out of, the idea being that one dressed “up” for the formal ritual of a multi-course meal. Moreover, the presence of ladies demanded better clothes. Ladies, the thinking went, have delicate sensibilities, and one always wanted to look one’s best for one’s sweetheart.

***INSERT IMAGE: Almack’s Ball, 1815***

The formal meals mentioned by Antongiavanni provide another clue as to the dominant status of evening clothes: among the leisure class dinner was not the end-of-day meal it is for us now but, rather, an event that divided the two halves of a day that began late in the morning and lasted well past midnight. Daylight hours were for business affairs and recreation while candlelight was dedicated to seeing and being seen at lavish repasts, opulent balls and private opera boxes. Being spent exclusively indoors and exclusively with peers, the latter portion of the day was by its nature the most formal and therefore demanded the most prestigious attire.

Regency Evening Dress

As he did with day wear, Beau Brummell revolutionized how a gentleman dressed after dark. His preferred evening costume was a more staid version of his daytime apparel and according to biographer Ian Kelly consisted of a dark blue or black tailcoat, white waistcoat, black pantaloons or black knee breeches with silk stockings, white cravat, and thin shoes. By 1801 Brummell’s outfit had become required attire at Almack’s, the most fashionable club in London thus laying the foundation for the black and white palette that governs evening wear to this day.

Brummell’s dress code did not gain universal acceptance overnight, though. In the century’s second decade the renowned dandy’s influence waned when he fell out of favor with the Prince Regent then ultimately ended with his self-imposed exile to the French coast to escape massive personal debt incurred from years of living far beyond his means. In his absence beaus on both sides of the English Channel began to bastardize the understated style that he had pioneered. Some of these Regency variations were soon discarded while others helped shape the evolution of today’s White Tie.

Varieties of Regency Dress

What’s in a Name?: “Sans culottes”

Sans culottes means “without breeches”. French revolutionaries were given this nickname because of their preference for long pantalons instead of the short breeches which were previously the norm and which became associated with the nobility.

On a related note, the French word pantalons was anglicized as pantaloons and later truncated to pants.

Revolutionary Fashion

The English nobility’s adaptation of the common man’s clothing was also inspired by British sympathizers of the egalitarian principles of French and American revolutionaries.

In their rejection of their colonial masters, American rebels turned to their French brothers-in-arms for their fashion cues which became ironic when the new French elite began importing the gentrified English look.

Dress Decorum

Regency evening attire was usually divided into three sub-categories: dinner dress for informal dinners and concerts, ball dress for formal entertaining and the opera, and court dress for formal Royal functions. The latter two were often termed “full evening dress”.

Court dress was the most formal level of dress in monarchies. It was distinguished by elaborate fabrics and ornamentation and by preservation of outdated sartorial traditions.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie