For men the proper costume for late dinner (at six o’clock or after) is regulation evening dress. At stag dinners and small informal occasions the dinner-jacket replaces the swallow-tail coat and is accompanied by a plain black-silk tie.

Good Form for All Occasions (1914)

Edwardian Etiquette

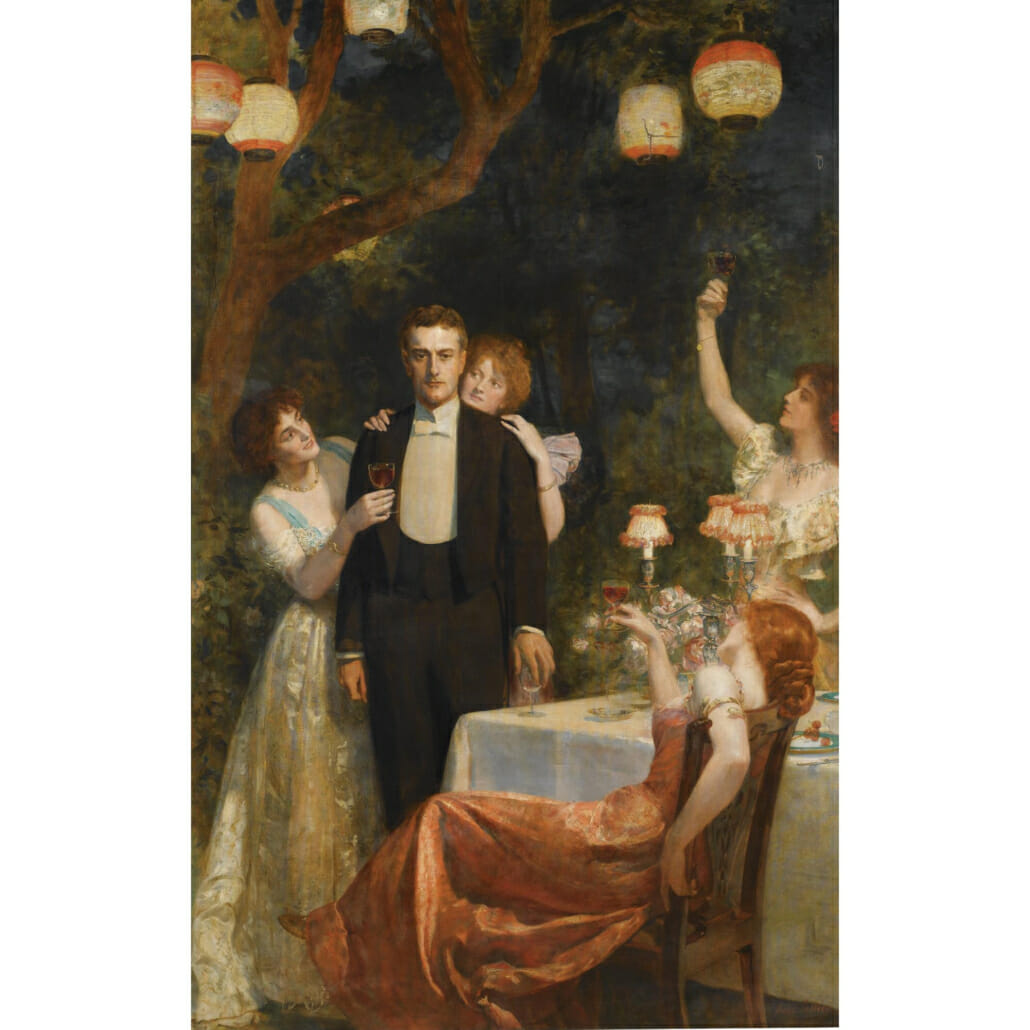

Edward VII’s affinity for wine and women loosened the moral strictures of his mother’s reign and the rise of the automobile shifted the focus of social life from the private home to more public places of entertainment. Despite these changes, dress codes generally retained their Victorian stringency thanks the new king’s taste for fine fashions and extravagant entertaining which the aristocracy eagerly adopted.

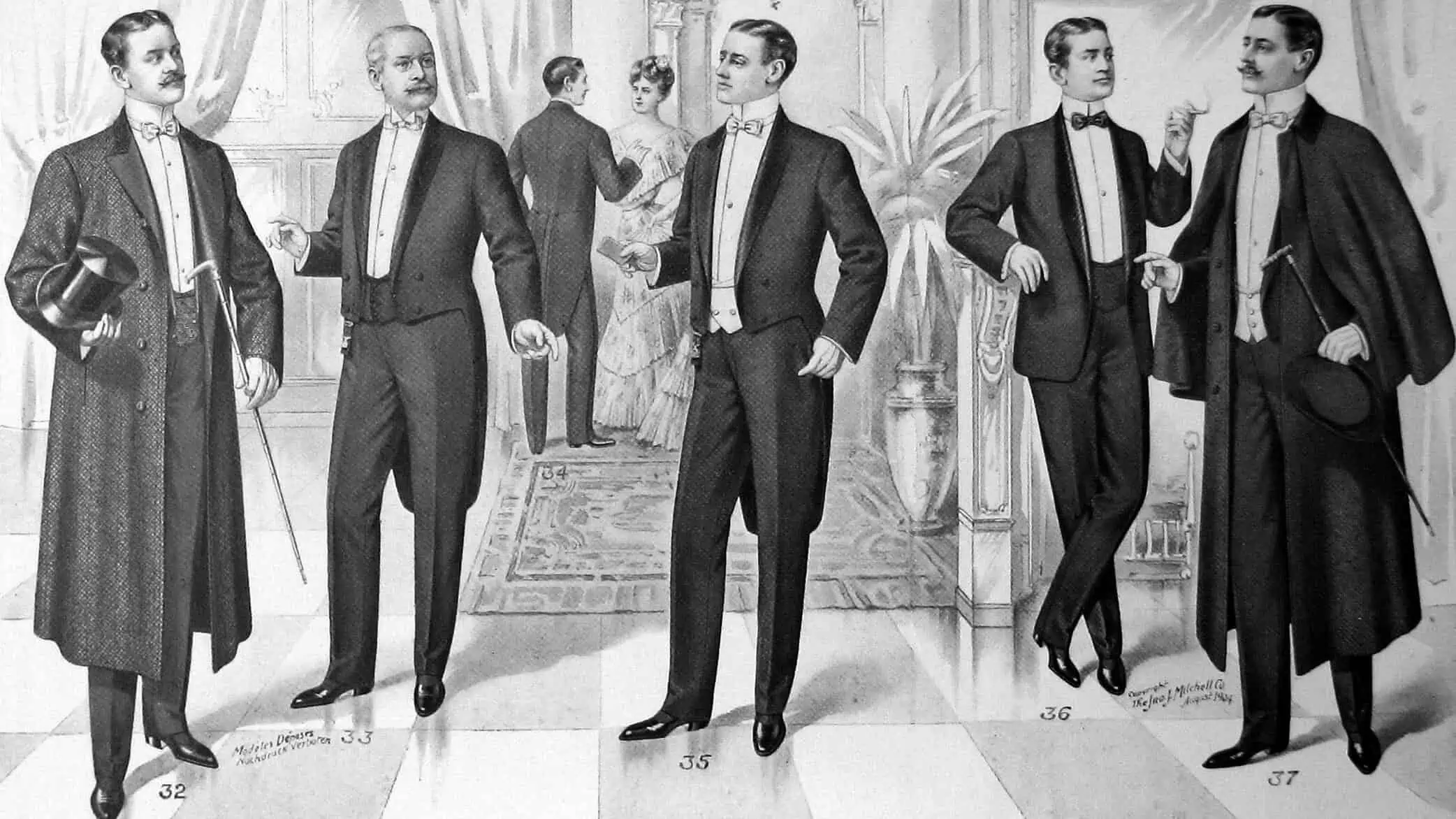

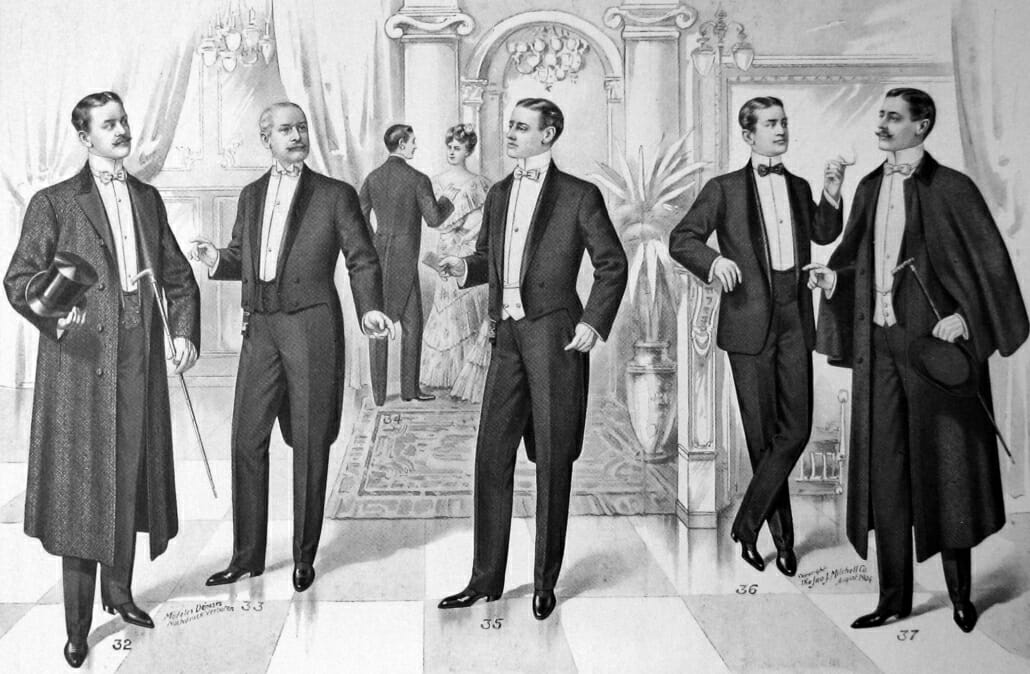

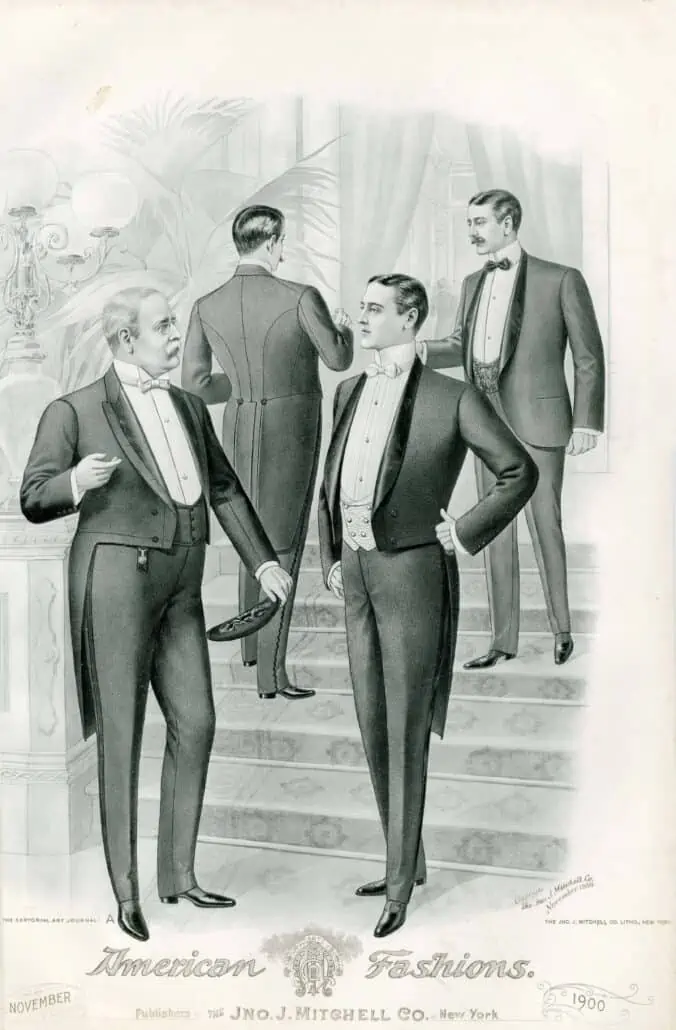

At the beginning of Edward’s reign, evening etiquette was the same two-tier system introduced in his mother’s era. The formal tailcoat ensemble remained de rigueur for an evening out in public alongside ladies’ elaborate evening gowns while the “dinner coat” or “Tuxedo coat” was largely confined to a man’s home, club or stag parties. Warm weather also exempted men from the full-dress rule, making the alternative jacket ever more popular at upscale holiday getaways on both sides of the Atlantic.

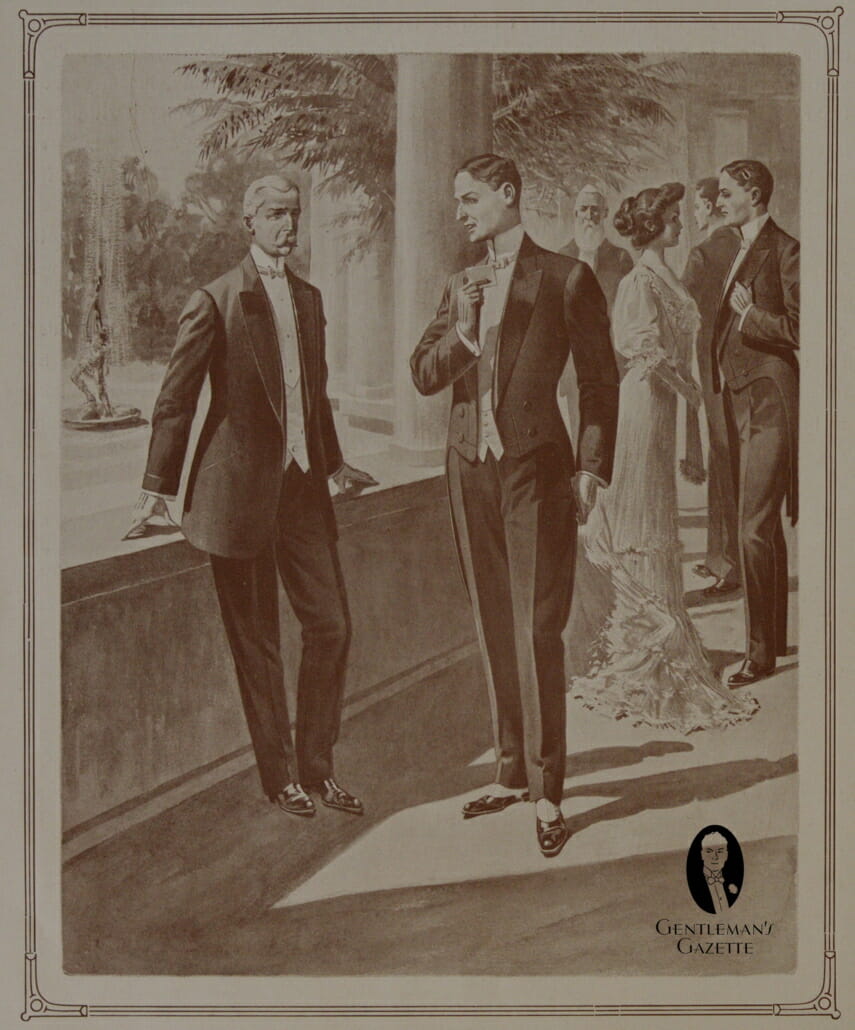

As the new century progressed, the dinner jacket exceptions increased, at least according to American etiquette manuals. Added to the list were standard evening entertainments in the country, very informal dinners among relatives or friends and dining in restaurants. Visits to the theater were acceptable under specific conditions: at first, only when a gentleman was not part of a theater party then even when he was, provided the party was small and was not occupying a box. With the increased popularity of the alternative jacket came an increased acknowledgment of its unique accessories as mandated by etiquette authorities. By the advent of The Great War, the public had finally embraced the two distinctive evening dress codes which remain in effect to this day.

The Components of Edwardian Evening Dress

The Unique Evening Suit

Evening suits in turn-of-the-century America differed from the common “lounge” or “sack” suit in that they were shapelier than their heavily padded and loose-fitting daytime cousins. One of the few traits that both had in common was the heavy fabric that weighed up to twenty ounces to the yard – twice the weight of the average modern suit. In this era, comfort was not expected in men’s clothing, night or day. While the following trends are based on American sources, the fact that the United States so closely mimicked English sartorial trends up until World War II makes it likely they were the same in both countries.

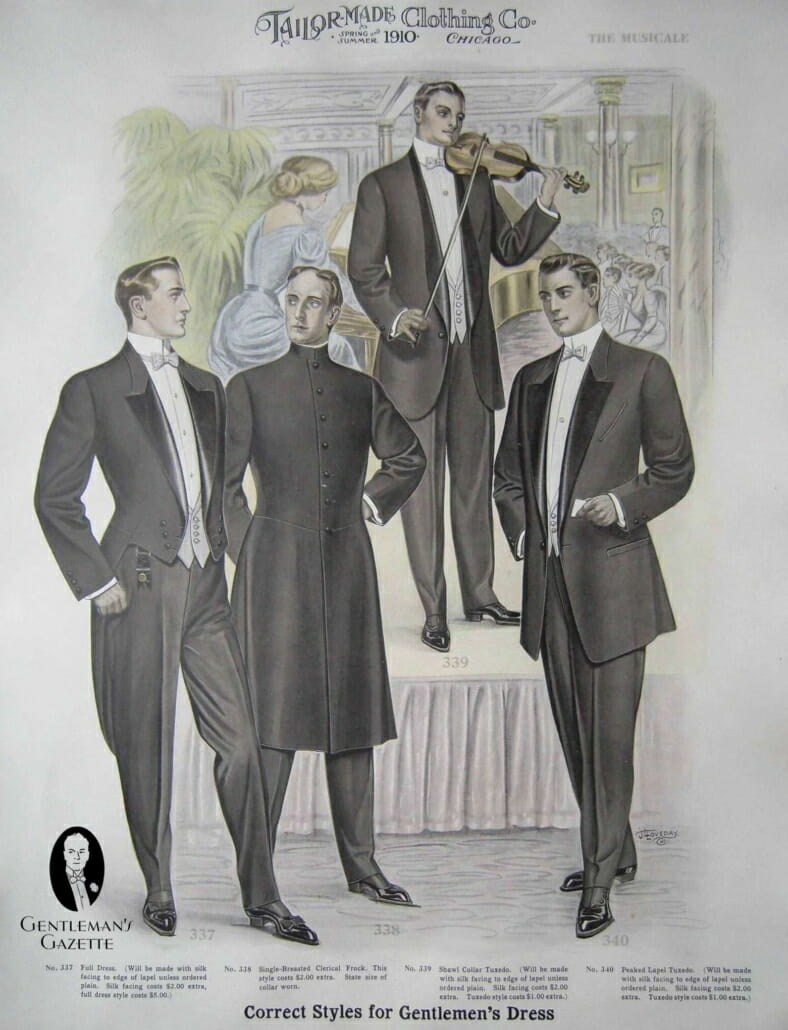

The evening tailcoat was still referred to as a dress coat or swallow-tail coat during this period, and sometimes a claw-hammer coat. The shawl collar option became increasingly rare and disappeared altogether during World War I. At the same time, the fronts of the coat (and accompanying waistcoat) began to angle upward towards the tails rather than being cut parallel to the waist. Three buttons on either side of the coat front became the norm by the teens. If present, side braid on trousers now took the form of either a single or double stripe.

The Accompaniments: White Waistcoats, Black Shoes

Waistcoats

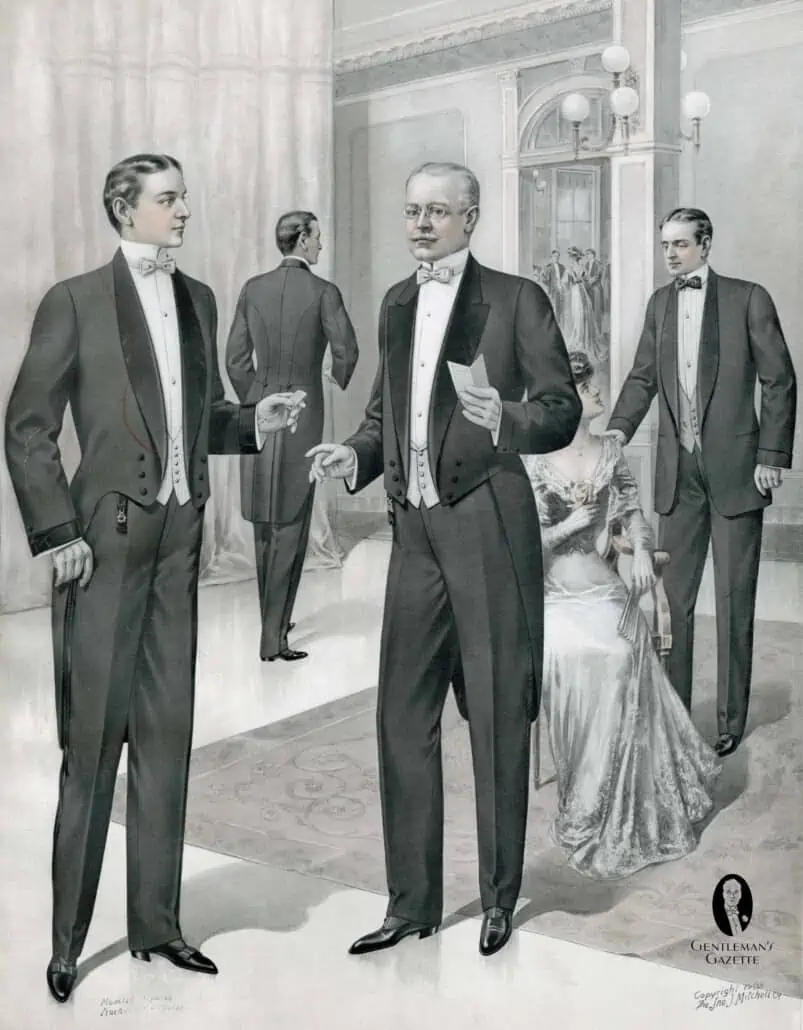

The English preference for white piqué waistcoats caught on in America and by the end of World War I, black waistcoats were becoming relegated solely to informal evening dress. Double-breasted styles had become as popular as single-breasted and both began to develop points at the bottom as their fronts followed the lines of the newly angled tailcoat fronts. The U-shape opening remained the favorite style.

Evening Shirts

The evening dress shirt still featured a stiff bosom of piqué or plain material and the number of studs ranged from one to three throughout the period. The shirt’s collar could be attached or detached with the wing collar gradually supplanting poke as the most popular style. Cuffs, conversely, were always to be attached when worn with evening dress. By 1913 a new trend had emerged which would prove permanent: the material of the shirt’s bosom, collar, and cuffs were to match that of the accompanying bow tie and waistcoat. Also appearing during this era were soft pleated dress shirts with French cuffs which were at first appropriate only with the dinner jacket but then became accepted by mavericks with the dress coat.

Shoes

Patent leather shoes eventually replaced dress boots of a like material and even began to encroach on the popularity of pumps. Outdoors, the silk hat continued to be standard for formal evening dress. The opera hat was still acceptable for theatre or opera but it was increasingly considered old fashioned.

Accessories

As for accessories, white or pearl kid dress gloves were still prescribed, especially for the opera and evening balls. Pearl, mother-of-pearl, and moonstone were the most popular options for studs and links which conduct manuals typically suggested be of a matching set. Watch chains worn across the waistcoat were no longer in fashion (“surely not in the evening” sniffed Vanity Fair); instead, timepieces were hidden at the hip and attached to the familiar watch fob or the newly popular keychain.

White boutonnieres were popular at Edwardian balls and according to the Handbook of English Costume in the Twentieth Century, “a red silk handkerchief was often worn as an ornament protruding from the bosom of the waistcoat”.

The Components of Informal Evening Dress

The most popular style of dinner jacket was still single-breasted peak lapel or shawl collar in black vicuna. Edwardian dandies also favored oxford gray, dark blue or double-breasted models. As long as the trousers matched the jacket it did not necessarily matter if they had braid on the outseams.

The prescribed accouterments for the jacket continued to be in flux during this period and were often the same as those worn with full dress. As in Victorian times, the waistcoat could match the jacket or it could be the white piqué style borrowed from formal evening dress.

And the choice of a black or white bow tie remained largely arbitrary despite etiquette authors insisting that only the former was appropriate for informal evening attire. However, the black waistcoat and black bow tie would become the norm for tuxedos by the end of the first decade, establishing the basics of today’s Black Tie dress code. Other traditions premiering during this era were the practice of matching facings on jacket lapels, bow tie, and trouser stripes as well as the wearing of low-crowned hats in place of the silk top hat.

The Great War: End of an Era

The rigid class system which defined Edwardian England came to a close with the advent of World War I. While the nation’s monarchy would survive the struggles that brought an end to a number of its European counterparts, its aristocracy would never be the same. The ability to host the lavish social affairs of previous times was greatly impacted by the tremendous cost of the war and by former household staff’s unwillingness to return to servitude after having fought shoulder to shoulder with their previous employers.

In addition, the constrictive and heavy attire that previously constituted formal day and evening wear was now unappealing to men of all classes who had become used to the easy-fitting mass-produced clothing popularized by military uniforms.As a consequence of these shifts in social norms, the tailcoat’s glory days as predominant after-dark attire would draw to a close. Conversely, the dinner jacket’s adroit balance of traditional elegance and contemporary comfort would elevate it from a mere dress-coat alternative to the new evening wear standard.

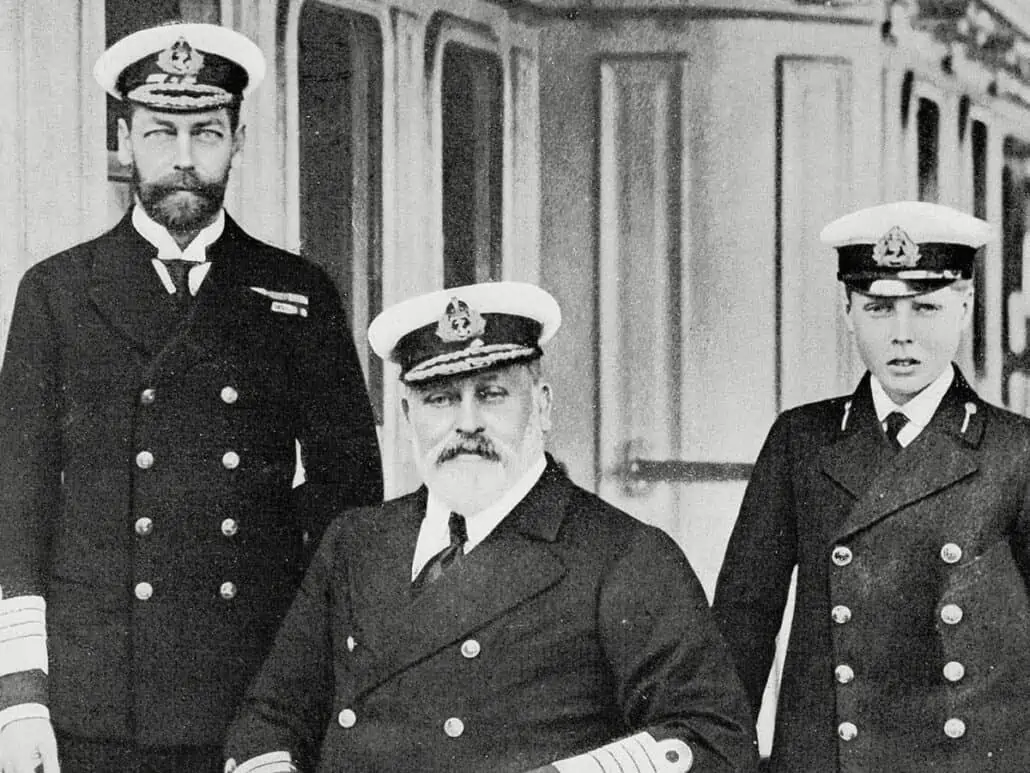

Edward VII

Edward VII (center) reigned from 1901 until 1910 although the eponymous era generally extends to 1914 and the start of WWI. He was succeeded by his son George V (left) then by his grandson the future Edward VIII and later Duke of Windsor (right).

Dress Decorum & Formal Facts

Dress Decorum: Edwardian Open Jackets

As in Victorian times, dinner jackets were invariably depicted as being worn open during the early Edwardian period and many models were actually constructed without buttons. By the teens, it was common for them to be fastened.

Formal Facts: The Advent of Evening Weddings

During this era, references to evening weddings first began to appear in etiquette books which mandated full evening dress for the groom and male guests.

Dress Decorum: Key Chains and Fobs

Key chains and more often fobs were often used to carry pocket watches. They were long, fine chains of gold or platinum attached to the suspenders and tucked into the trouser pocket with the watch.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie