A dinner-jacket used to be the sign of extreme informality in the evening. A man might put it on for dinner at home and change it for a dress-coat if he went to the opera or a dance afterward. Now it has become so usual an evening garment that, except on most ceremonious occasions, most young men wear it habitually. Vogue’s Book of Etiquette (1925)

Vogue’s Book of Etiquette (1925)

A New Standard for Evening Wear

Occasion

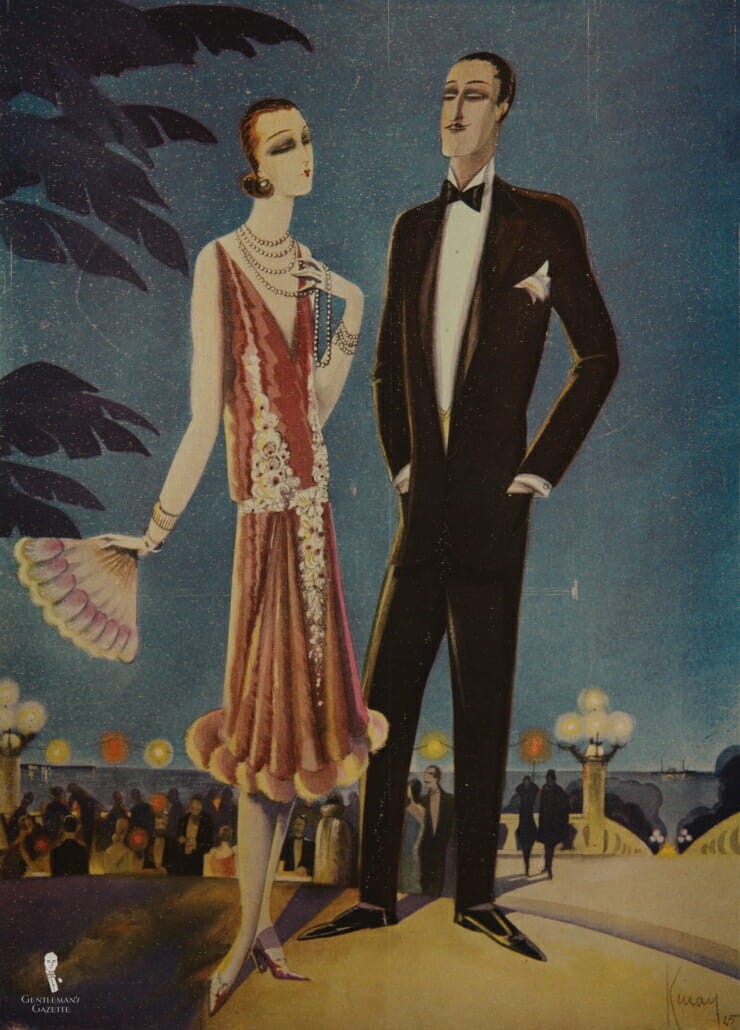

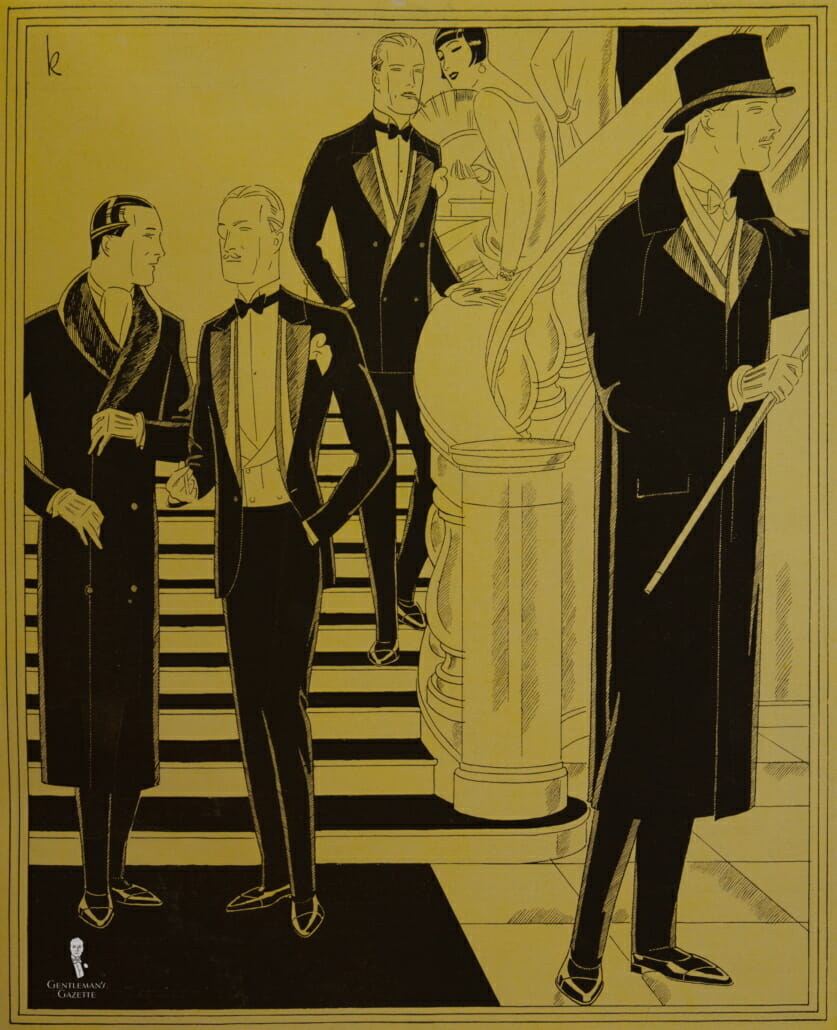

The new world order that emerged from World War I was a youthful one epitomized by the innovation and energy of America’s wildly popular jazz music. The rigid formality of Edwardian evening entertainment and attire became a casualty of war on both sides of the Atlantic; consequently, the formerly de rigueur tailcoat ensemble was consigned only to extremely formal functions. In its place, the dinner jacket which had been previously considered too vulgar for female sensibilities was promoted to the role of standard evening attire. As Emily Post advised in the 1922 first edition of her definitive Etiquette series, “To a man who can not afford to get two suits of evening clothes, the Tuxedo is of greater importance. It is worn every evening and nearly everywhere, whereas the tailcoat is necessary only at balls, formal dinners, and in a box at the opera.” A dress coat was also mandated for evening weddings as the wearing of dinner attire in church was still considered impertinent by polite society.

A Vogue article lamenting the decline of masculine elegance posited a number of theories for the tuxedo’s domination of the tailcoat: the inappropriateness of dressing formally for evenings during wartime, the dress coat’s lack of suitability to all physiques compared to the equalizing attributes of the dinner jacket, the (mistaken) perception that more effort was required to don full-dress, and a fear of being labeled as old-fashioned. The resulting preference for the tuxedo disheartened the author who felt that the less formal jacket “gives all the men such a monotonous and tiresome aspect as if they were clerks who had simply changed their coats.”

Such proponents of Edwardian gentility were fighting a losing battle. In fact, the wearing of an evening tailcoat anywhere other than prescribed was now considered a faux pas. “People of the social world are supposed to dress for each other, not for the populace” explained Vogue’s Book of Etiquette in 1925. Thus, when in their private opera boxes and orchestra stalls such people were among friends and could dress as if they were socializing at home. In restaurants or theatres, however, they may or may not be exclusively among their peers therefore good taste dictated they moderate their full finery so as not to appear conspicuous. “Overdressing in public places such as restaurants, hotels, [and] steamers, is generally done by people who have only this opportunity of exhibiting themselves.”

Attire

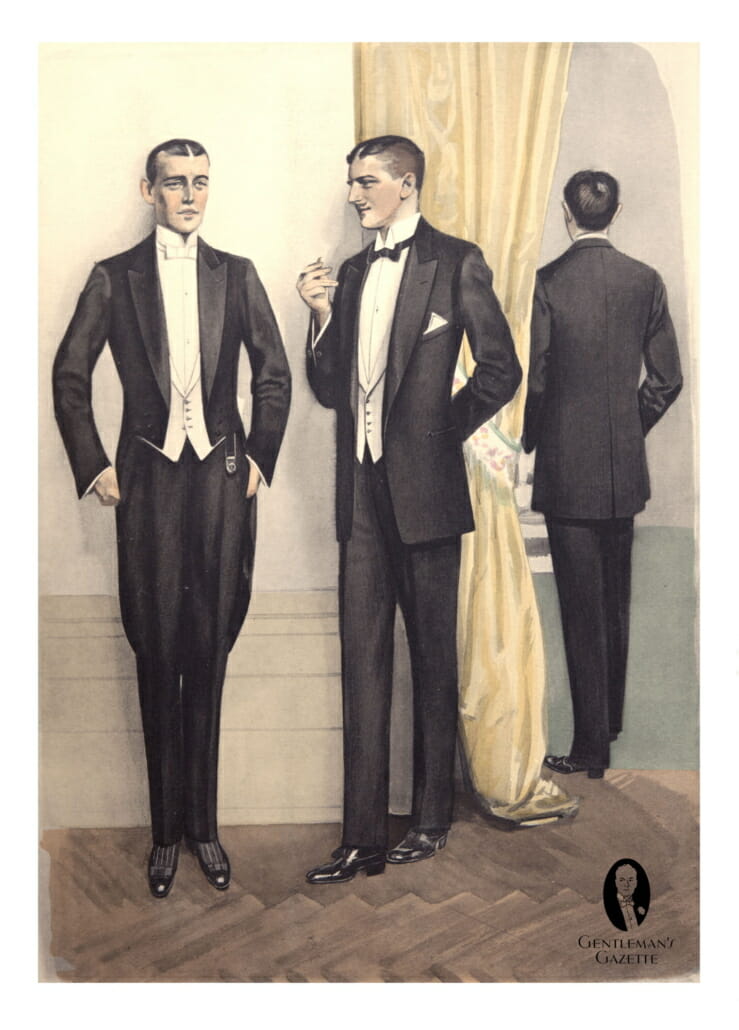

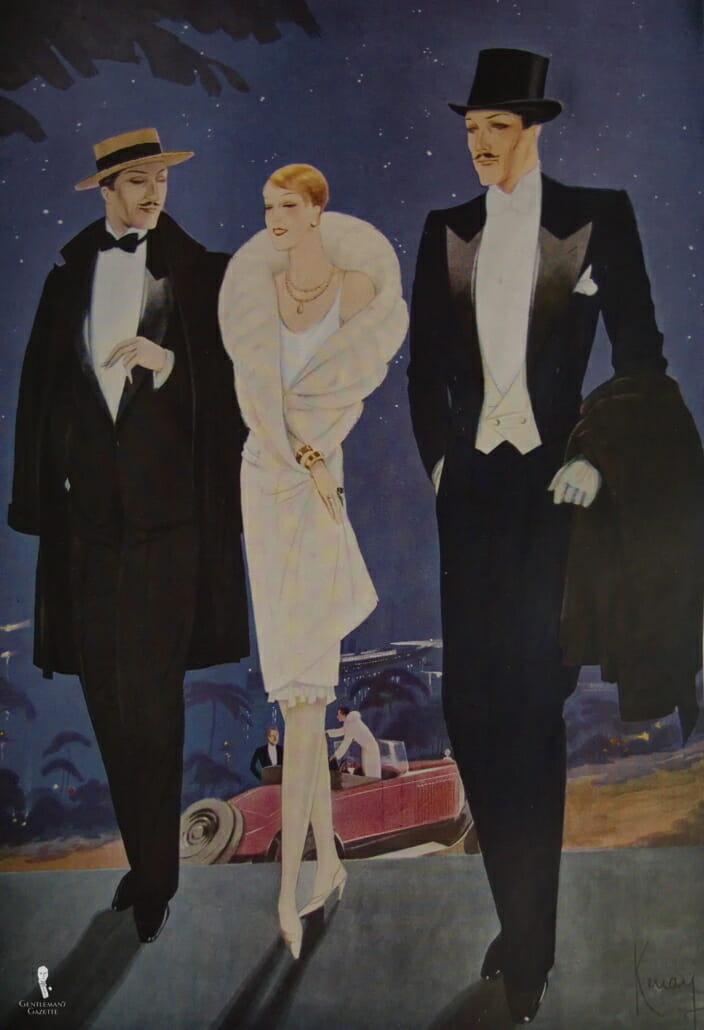

Despite the reversal of their popularity, the classification of the dress coat as formal and the tuxedo as informal remained unchanged. Interestingly though, the tailcoat ensemble also became known as “full dress” once again, a befitting moniker for its new exclusive status.

The rules for corresponding accessories also remained the same at first. One notable exception was the renewed allowance for the white waistcoat to be worn with a dinner jacket. This popular practice of the early years, combined with a corresponding preference for peaked lapels instead of shawl collars, was seen by period authorities as an attempt to impart the formality of the full-dress outfit onto its replacement.

Evening wear protocol then took a decidedly informal shift as the decade progressed, thanks in large part to a stylish young Prince of Wales known as the twentieth century Beau Brummell.

Roaring Twenties Style

David, Prince of Wales

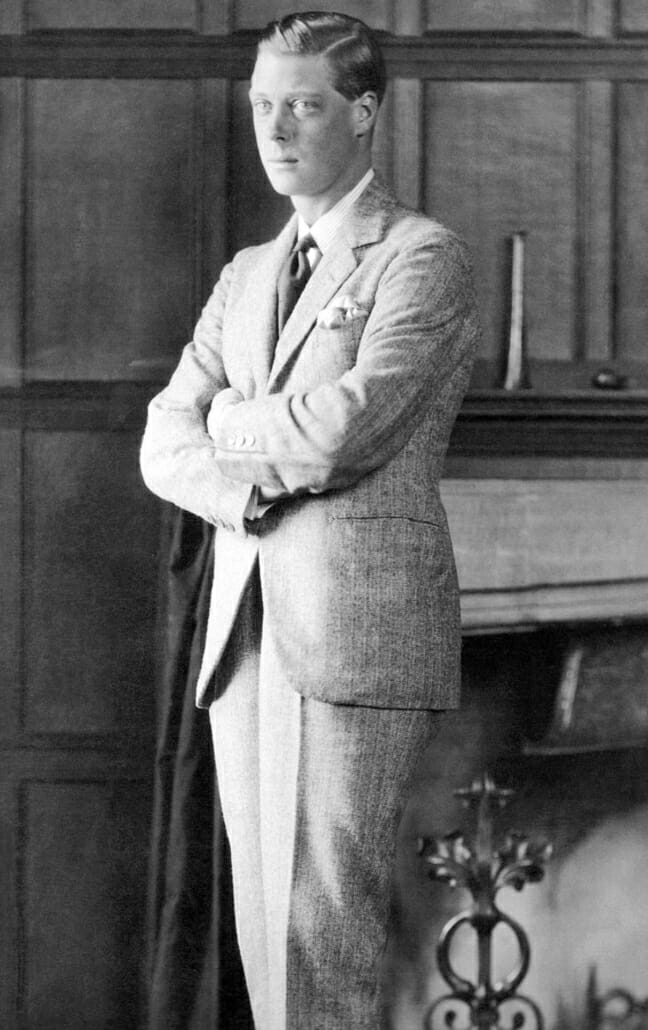

After the death of Edward VII in 1910, his son George V worked diligently to restore the formality and discipline that his father had let slide at Court. However, George’s own heir shared more than his grandfather’s name (see sidebar). The new Prince of Wales also enjoyed the elder Edward’s preference for sartorial style and comfort over stuffy tradition and beginning in the 1920s this maverick’s impeccable fashion sense would influence menswear for years to come.

By regularly opting for the dinner jacket over the full-dress coat, the future Duke of Windsor and his aristocratic circle of friends played a pivotal role in its elevation to standard evening wear. The adoption of the practice in the United States was then only a matter of time since style-conscious Americans were greatly influenced by British trends during this period. Numerous other changes in evening fashions soon followed as the Prince and other British trendsetters skillfully set about improving formal attire’s comfort and enhancing its panache.

Rhapsody in Midnight Blue: A New Color for Black Tie

One of the first evening wear innovations championed by the Prince was an alternative to its standard black shade. Midnight blue – a deep, blackish blue – was appropriately muted hue for formal attire yet appeared darker and richer than black under artificial light because it did not have the latter’s tendency to give off a greenish cast or show up dust. The revival of this Regency-era fashion was limited to select English aristocrats and dandies at first but the color’s popularity grew steadily over the twenties foreshadowing its mass appeal in the following decade.

White Waistcoats for Black Tie

During the 1920s, the white waistcoat had come to be considered the most formal color because unlike its ebony counterpart, it required frequent laundering and starching and therefore more expensive. Consequently, black models ceased to be an alternative for full-dress suits while white models became increasingly popular with dinner jackets, especially at occasions which had previously required tailcoats.

In April 1924, Men’s Wear reported that adoption of the tuxedo and white waistcoat trend by such fashion leaders as the Prince of Wales and Lord Mountbatten had made it widely acceptable in London and that half of waistcoats observed in a survey of Palm Beach informal evening dress were of the ivory variety.

A stylish mode for the white waistcoat was the straight-waistlined “tub” fashion that had been revived in America in 1921, a year after its re-introduction in England. Available in single- and double-breasted models it was popular with both informal and formal evening dress because its high-waisted cut and lack of points could better accommodate the height and fullness of the new trouser style.

A few years later, another waistcoat innovation was rapidly gaining in popularity: the backless model. Yet another contribution from His Royal Highness, this design replaced the full back of the waistcoat with just two small straps that held the front in place thereby allowing the vest to retain much less body heat and making it particularly ideal for tropical climes.

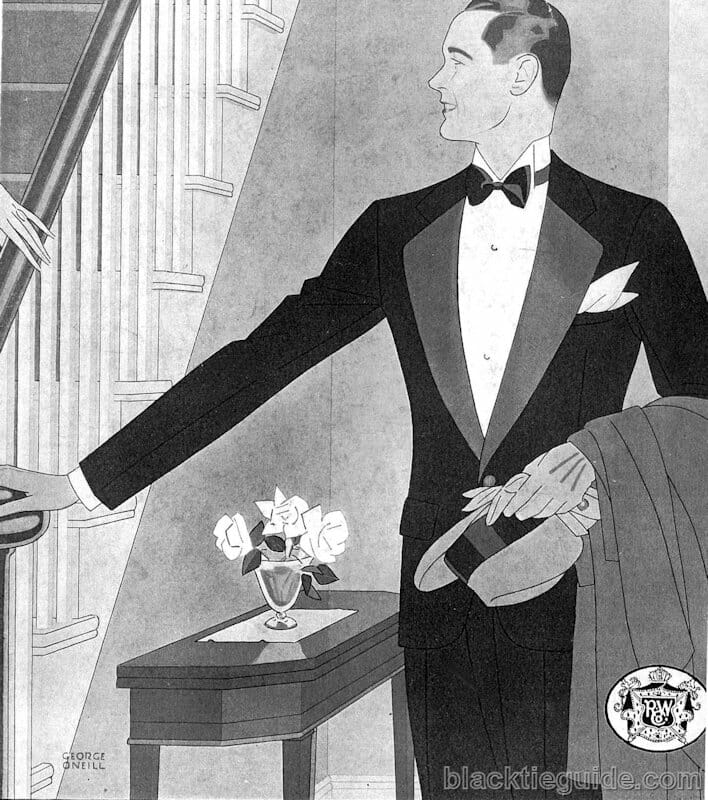

Rise of the Double-Breasted Dinner Jackets and Soft-Front Shirts

In 1928, the Prince of Wales publicly condemned the “boiled shirt” of his ancestors and two Men’s Wear surveys from that year revealed that American men seemed to share the sentiment. The periodical reported that while most men continued to favor wing collars and stiff-bosom shirts with their dinner jackets, some of the younger generations had taken to wearing negligee shirts with soft attached collars. The magazine’s editors scolded that “This style mirrors the quintessence of informality, in fact, these men could hardly adopt any more radical style and still be ‘properly’ dressed.”

The editors pointed out that this trend away from traditional formality was further emphasized by the increase in popularity of double-breasted dinner jackets, an American invention that had first appeared at the turn of the century and which was usually worn without a waistcoat. Etiquette authors were equally disapproving and advised their own readers that the appropriateness of both the new jacket and the soft or pleated shirts was strictly limited to summer evenings and other equally informal occasions.

A Decade of Trends

Minor fashion developments that applied to both informal and formal evening dress in the twenties included bolder wings on shirt collars, wider bow ties, the appearance of button trim to match lapels (although some etiquette sources only accepted bone buttons on the tailcoat) and an increasing preference for laced shoes in place of pumps or button shoes.

In regards to full dress, the tailcoat’s front was cut shorter to accommodate higher trousers which could feature either two narrow braids as before or one broad braid (as opposed to one optional narrow braid on dinner trousers). Some affluent men continued to wear shirt bosoms, waistcoats and bow ties of matching piqué although the high cost of these custom-made sets limited their popularity.

As for the dinner jacket, it began sporting a link closure (a buttonhole on either side of the jacket front fastened by a cufflink-like accessory called a “coat link” or “link button”) and was now usually buttoned up. The addition of a breast pocket during this decade prompted the debut of the formal pocket square. Also appearing at this time was a new take on an old Victorian accessory called a cummerbund. A 1928 issue of Men’s Wear explained to readers that this was a black silk sash used as a replacement for the waistcoat on warm evenings. While it may have made a slight gain in acceptance among the fashionable Palm Beach crowd that year it would remain largely confined to the sidelines until the following decade.

Dawn of the Golden Age of Menswear

The movement towards informal variations introduced in the 1920s would provide increasing comfort, variety, and style in the following decade and the tuxedo would gain popularity with a wider range of society than ever before. At the same time, the full dress would reclaim some of the formal tradition it had lost during the war. Evening wear was about to enter its greatest era in modern history.

Formal Facts

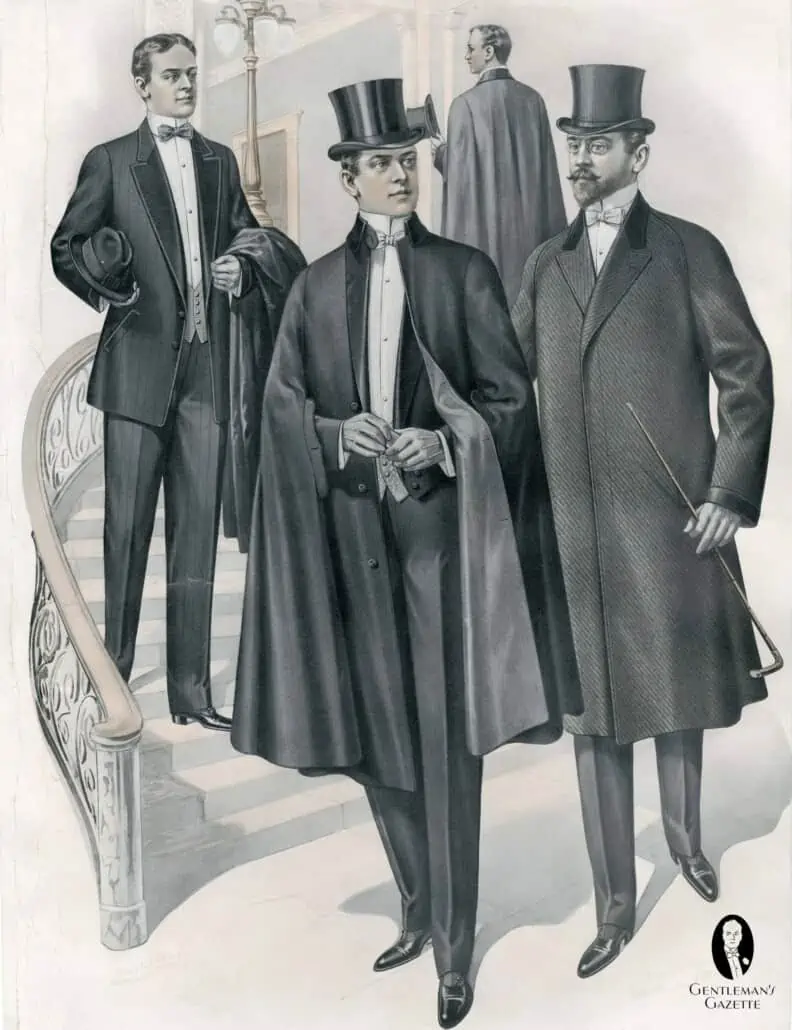

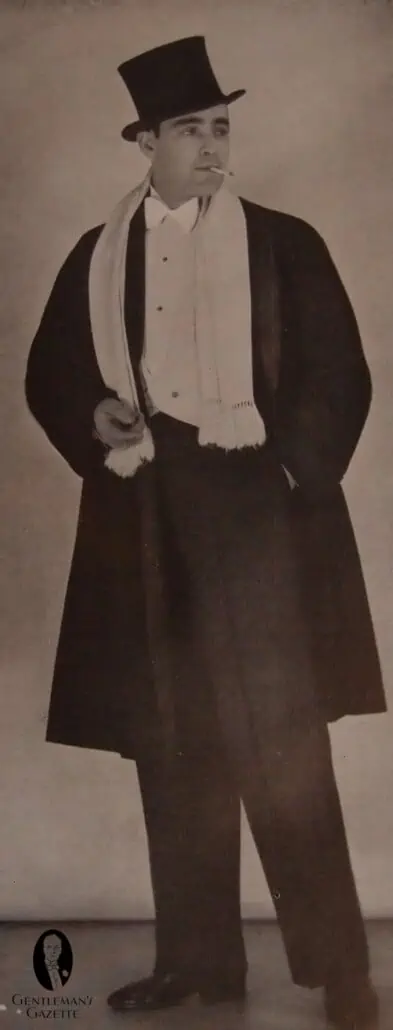

Overcoats or Capes were still Mandatory for White Tie in the 1920s

1920s etiquette required that an overcoat always be worn with a full dress. A typical evening overcoat was typically single breasted in earlier decades with a hidden fly, and sometimes featured raglan sleeves. The lapels were often faced with silk now. Sometimes, a contrast velvet collar was used instead.

By the 1920s men experimented with double breasted evening overcoats or shawl collars, but the popularity was somewhat declining by then and young men would skip the overcoat with white tie.

For black tie, overcoats were not mandatory anymore by the 1920s.

Original Tuxedo Rag

A 1920s jazz band’s formal attire was the inspiration for their name, The Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra, as well as one of their infectious tunes, “The Original Tuxedo Rag”.

1920s Style Icons

David, Prince of Wales

The Prince of Wales was probably the most photographed person in the world at the time. His sense of fashion and style impacted his generation. His full name was Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David Windsor but he went by David until he became Edward VIII in 1936. David was not a fan of the stiff white tie outfits, and preferred to softer, more comfortable black tie. He also preferred wearing a morning coat in lieu of a frock coat.

Overall he was a force for more casual, comfortable men’s clothes, but considering the formality of a tuxedo and morning coat today, it becomes obvious that change is often incremental rather than radical.

Jack Buchanan

Jack Buchanan was another British fashion maverick. He was a star of stage and screen in the U.K. and in the U.S. and is credited for introducing the double-breasted dinner jacket to England.

Well Suited: Perfection or Nothing

Period etiquette guides warned that unless a dress suit was perfect in fit, cut and material it was better not to wear one at all.

Original Tuxedo Rag

Jazz in the 1920s

A 1920s jazz band’s formal attire was the inspiration for their name, The Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra, as well as one of their infectious tunes, “The Original Tuxedo Rag”.

The Notched Lapel

Notched lapels (step collar in UK) had been available on dinner jackets since the early 1900s but were rarely endorsed by menswear periodicals, ignored by etiquette books and generally shunned by best-dressed men according to numerous Men’s Wear surveys. They all but disappeared after 1930 and didn’t re-emerge until the 1960s.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie