During the war, for various reasons, dinner jackets were rarely worn in public places

Vogue’s Book of Etiquette (1948)

. . . and this custom has taken root in America, particularly among the younger generation.

Spoils of War: The United States and International Fashion

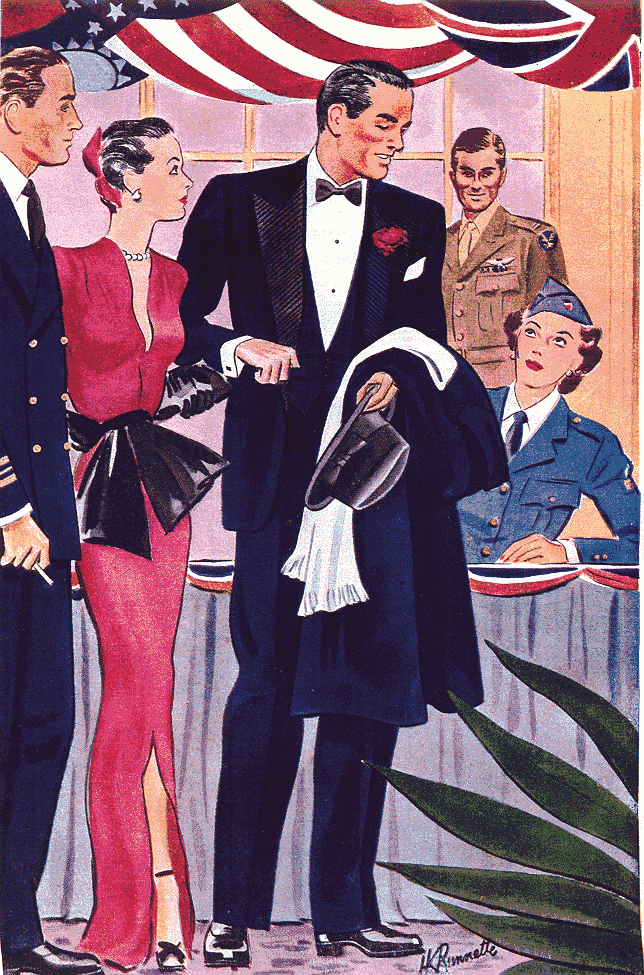

After the Second World War, the industrial juggernaut that had built America into a military superpower was converted to the production of consumer goods to feed the reconstruction of Europe and Japan resulting in an unprecedented economic boom. The patriotic pride associated with this victory of a youthful, democratic nation over historic, aristocratic empires encouraged Americans to begin celebrating their culture for its own unique merits. For fashion this meant a relaxed formality tempered by Cold War conformity.

Postwar Tuxedo Standards

Wartime Informality

America’s declaration of war in December 1941 signaled the end of evening wear’s heyday in that country. With the nation focused on winning the conflict abroad, formal fashions were limited by War Production Board regulations that prohibited textile-intensive garments such as double-breasted jackets and formal-front dress shirts. Many men simply mothballed their after-six apparel altogether, a trend noted in a November 1942 Esquire pictorial titled “Putting Emily on Ice”. Accompanying illustration of an informal couple dining in a fine restaurant was the caption “Wearing street clothes instead of the once de rigueur formal attire, this man and his partner assume an Emily Post-mortem attitude about the whole thing, as do many others in this new era of simple taste.” The only formal wear to be seen in the picture was the tailcoat worn by the couple’s waiter.

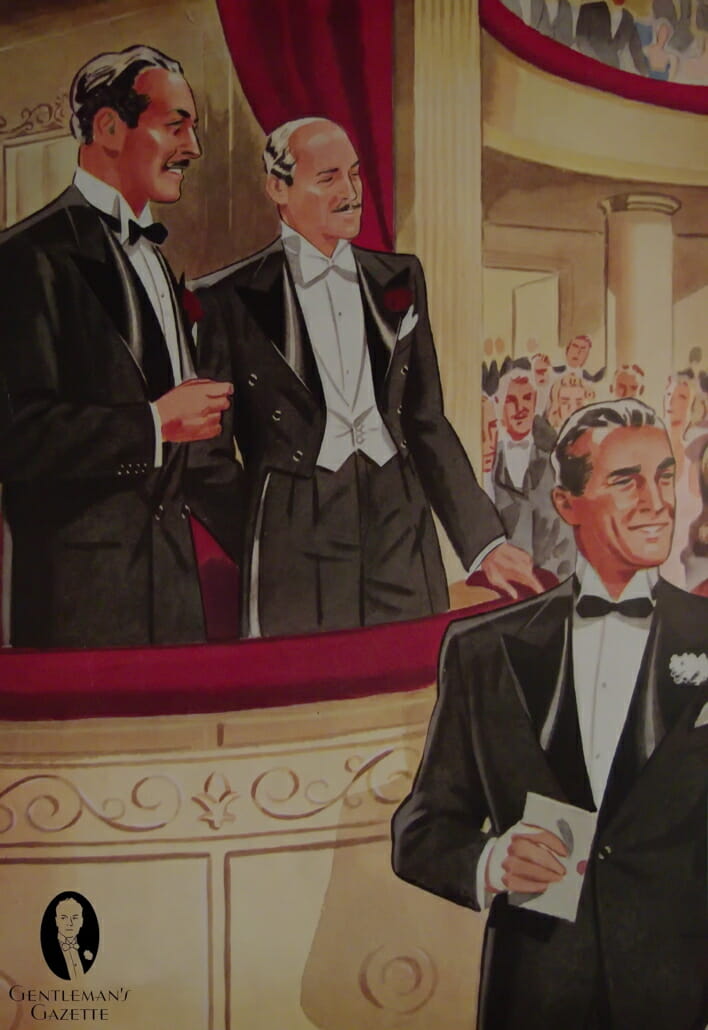

White-Tie Rarity

Unlike the aftermath of World War I when it gradually regained its lost popularity, full dress never recovered from its Second World War setback. The tailcoat’s patrician cast was now “thought to offend democratic tastes,” explains menswear historian Nicholas Antongiavanni, and thus even in the highest social circles it “was in Europe relegated to the grandest parties, concerts, and occasions of state, and in America to charity banquets.” Period conduct guides indicate the author’s summarization of stateside etiquette was a bit extreme, but not far off the mark. “The modern trend is to wear ‘tails’ only for the most formal and ceremonious functions,” stated The Standard Book of Etiquette in 1948, “such as important formal dinners, balls, elaborate evening weddings, and opening night at the opera.” Other authorities noted that even for these exclusive events organizers were often forced to modify the dress code to allow Black Tie as an alternative so as to avoid putting off younger men.

The subsequent history of White Tie is essentially a protracted death watch as the few remaining tailcoat traditions gradually fade away with each passing decade.

Semi-Formal Relativity

The tuxedo fared much better than its progenitor after 1945 but was significantly impacted by the wartime preference for regular suits as acceptable evening attire. In 1948 Vogue’s Book of Etiquette described the new postwar standard:

During the war, for various reasons, dinner jackets were rarely worn in public places. In restaurants, at the theater, even at first nights, they became the exception rather than the rule. And this custom has taken root in America, particularly among the younger generation. Although dinner jackets are never incorrect for the theater or dinner in a restaurant, they are usually worn in public only on special occasions.

The dinner jacket’s new status led to an interesting conundrum for etiquette authorities. On one hand, traditionalists were not yet ready to water down the customary “formal” label by expanding it to include the tuxedo. Conversely, it was illogical to continue referring to the outfit as “informal” now that the acceptance of the common suit had elevated black tie to the level of extraordinary evening wear. The solution for most experts was to adopt the “semi-formal” classification that sartorialists had begun using in the 1930s. While the term had become common by the early fifties its effectiveness was limited because it overlooked a more general shift in social standards. The 1955 edition of Emily Post’s Etiquette reveals the quandary:

Merely to clear away much confusion: Semi-formal does not mean women in formal evening dresses and men in business suits. In communities where the tail coat is worn, semi-formal means dinner jackets (tuxedos) and simple evening dresses. In others where the dinner jacket is formal, semi-formal would mean men in dark sack suits and women in so-called cocktail dresses.

The need for this advice reveals the increasing relativization of formality following the war: With every passing decade standards of behavior would be dictated less by a like-minded social elite and more by the democratic tastes of disparate socio-economic groups. The result would be an ongoing dilution of universal conventions and increasing confusion on the part of young adults seeking social guidance.

Forties Full Dress

Dandy shawl lapels, dramatically high waistlines, exaggerated collar wings, and showy blue boutonnieres were among the golden-age stylistic flourishes that faded into history at the close of the 1930s marking a return to more conservative full dress. Postwar developments were relatively few, the most notable being the allowance of satin trouser stripes and well-polished calfskin footwear as alternatives to traditional braids and patent leather.

The declining interest in full dress, along with its highly conservative nature, meant that these would be the last stylistic innovations of any significance. Consequently, the mid-fifties interpretation of White Tie remains the standard to this day.

Black Tie Goes Bold

The Bold Look

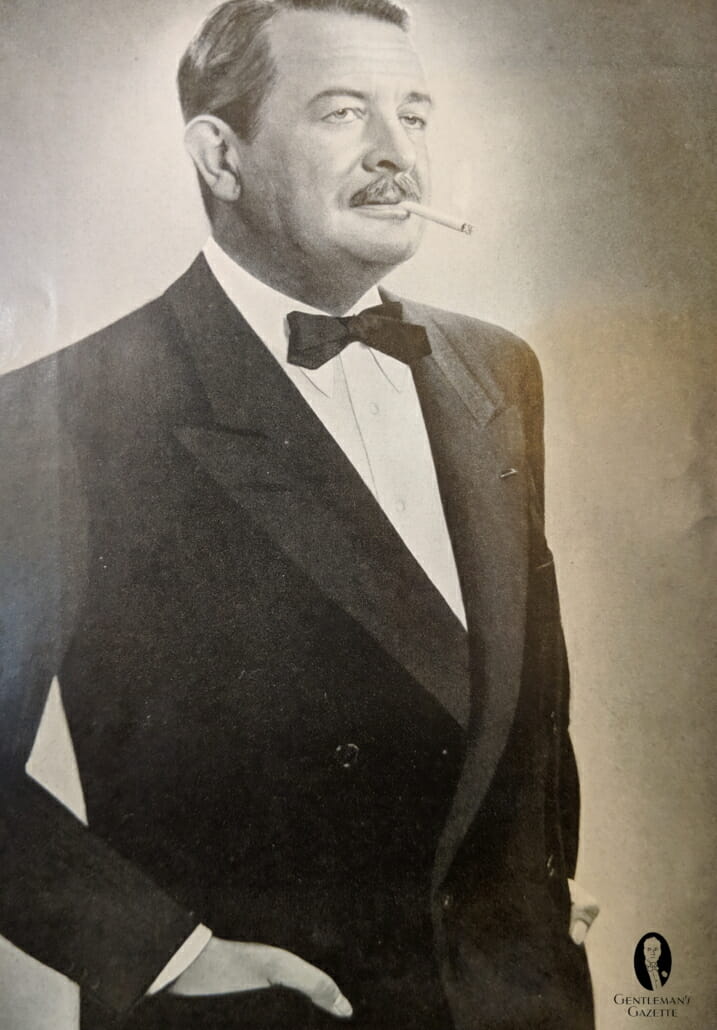

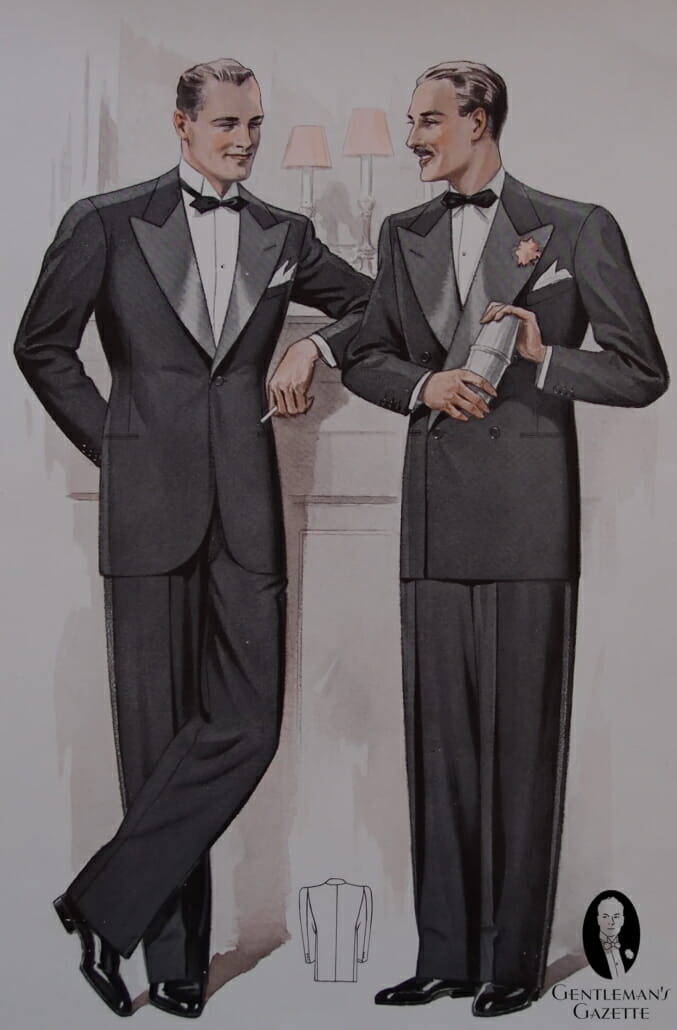

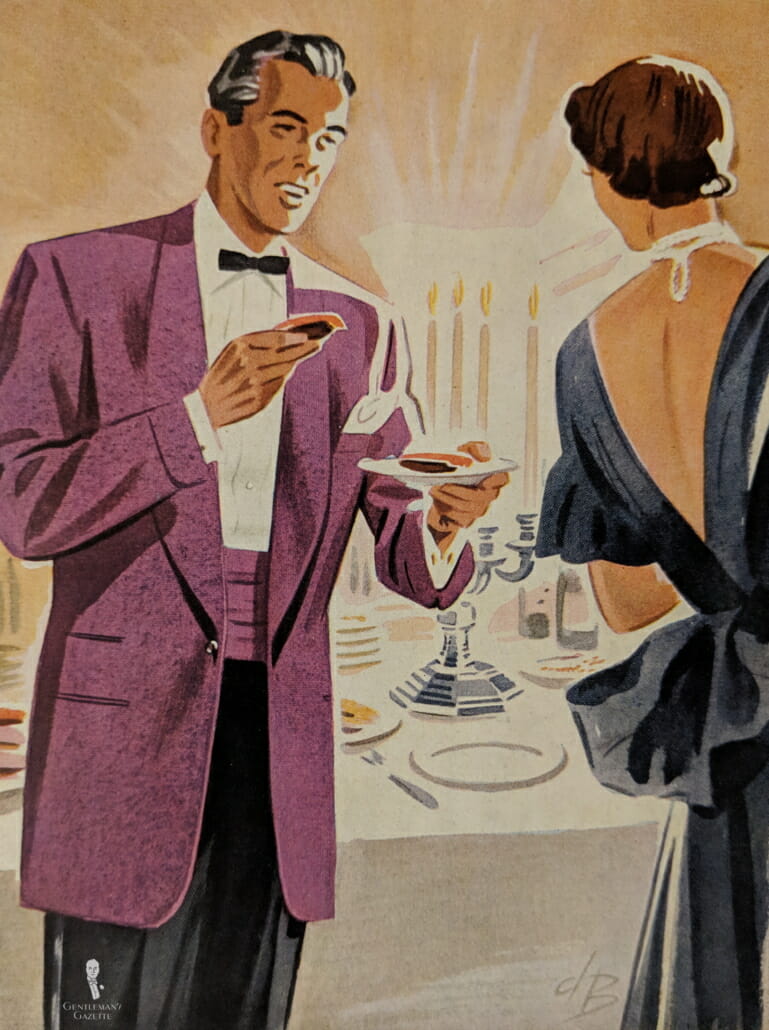

Although no longer the status quo evening attire, the dinner jacket was by no means out of the picture as postwar celebration and prosperity provided plenty of excuses for Americans to dress up once again. With the end of fabric rationing, the boxy double-breasted with wide lapels became the dinner jacket of choice particularly after Esquire launched the “Bold Look” in 1948. This uniquely American style of men’s wear brashly manifested itself in “wide borders, big patterns, bold colors”.

That same year the encyclopedic Vogue’s Book of Etiquette listed some relatively new dinner shirt alternatives. Besides the formal stiff-front shirt with wing collar and the less formal semi-starched pleated model with stiff fold collar, the postwar man could also choose a soft-collar shirt either in silk – with plain or pleated bosom – or in broadcloth. According to the book, the latter was “the most informal and probably the most usual.”

Trim and Relaxed Style

Other than the new shirt options, semi-formal evening wear in the late 1940s was pretty much identical to its pre-war incarnations. Styles did not truly begin to change until 1950 when Esquire introduced two new concepts in men’s fashion. One was the “Mr. T” look; a conservative silhouette featuring natural shoulders and trim straight lines. The other was the “American Informal” concept that highlighted “the greatest trend to date in men’s fashions: American Informality built right into even your dress and ‘formal’ clothes.”

The impact on evening wear was evident in both comfort and appearance. Formalwear worsted became lighter during the decade eventually weighing in at ten ounces to the yard. The visual manifestation of this slightly relaxed formality was a preference for the slimming single-breasted jacket with streamlined shawl collar and understated cummerbund. Add to this a turndown collar shirt and narrow bat wing tie and the result was the quintessential fifties tuxedo.

Summer Semi-Formal: Black Tie in Warm Weather

Thanks to the availability of tropical worsted and the relaxed standards of formality introduced by the war, warm-weather attire became increasingly popular in the postwar years. As before the war, white single or double-breasted shawl collars were still the preferred models for summer dinner jackets. Postwar etiquette and style authorities also continued to allow colors in accessories although they were now generally limited to black, midnight blue or maroon.

The informality of warm-weather black tie provided a launching pad for some significant innovations in the early fifties. Esquire introduced a subdued tartan dinner jacket as well as plaid cummerbunds with matching bow ties. At the same time, formalwear manufacturer After Six began advertising red and blue jackets for summer. These notable departures from tradition would prove to be a harbinger of fashions to come.

Ready for Change: Rapid Evolution of Evening Wear

The first ten years following the war was a period of transition for American formal wear. The brash new superpower was ready to reinvent British tradition in its own uniquely informal image but wasn’t quite sure how to do it. To wit, while the habit of when to wear evening dress was quickly redefined, the practice of what to wear was primarily a shift toward pre-war casual styles. There was little originality in formal fashions during this period and the return of Esquire’s “correct dress” charts in 1952 was a reminder that conformity was the duty of every patriotic American in the ongoing covert struggle against communist infiltration.

After a decade of such caution though, the country began to grow restless with the prevailing conservatism and black-tie fashions were set to catch up with the modern age.

Debutante Balls

Debutante balls date back to at least 1780 when King George III held the first annual ball for daughters of the well-bred to be presented to the Court thus making their “début” into society (and beginning their search for a suitable husband). The American upper class adapted many of the English traditions at similar balls often referred to as cotillions.

Prom Evolution

By the 50s, Americans were enjoying more affluence than ever and the stature and fancy nature of proms grew in relation. Note the trendy tartan cummerbund and bow tie on the lad on the left.

New Looks for a New Age

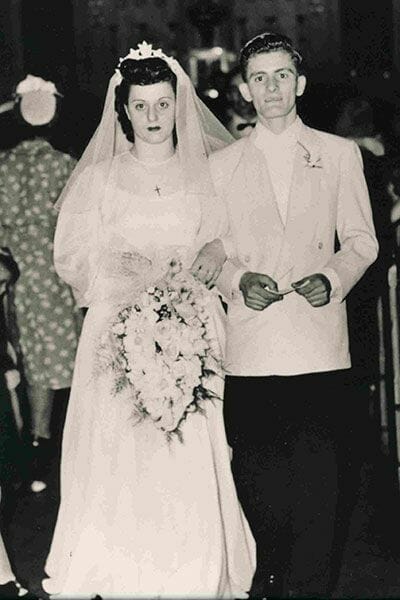

Evening Weddings

Formal summer weddings grew increasingly popular through the forties despite the traditional taboo on wearing tuxedos in church. See Vintage Evening Weddings for details.

The Bold Look

According to Esquire‘s understated editors, this new look rejected the “stilted traditionalism” of “European court dandies and of a pallid, ineffectual continental society” in favor of a home-grown “virile” and “masculine” look befitting of men who “have hacked and hewn a nation out of wilderness and smashed their way to a world dominance”.

Formality At Sea

According to 1953’s Esquire Etiquette, “On most transatlantic and cruise ships, a dinner jacket is the norm after six in first class – optional in cabin class – very likely show-off in tourist class.”

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie