Protecting your Black Tie ensemble – and yourself – from the elements is the primary goal of evening outerwear, although a stylish apperance is a very close secondary concern. In this section, you’ll learn about how the common types of evening outerwear have developed, keeping gentlemen warm while looking elegant.

The Evolution of the Evening Hat

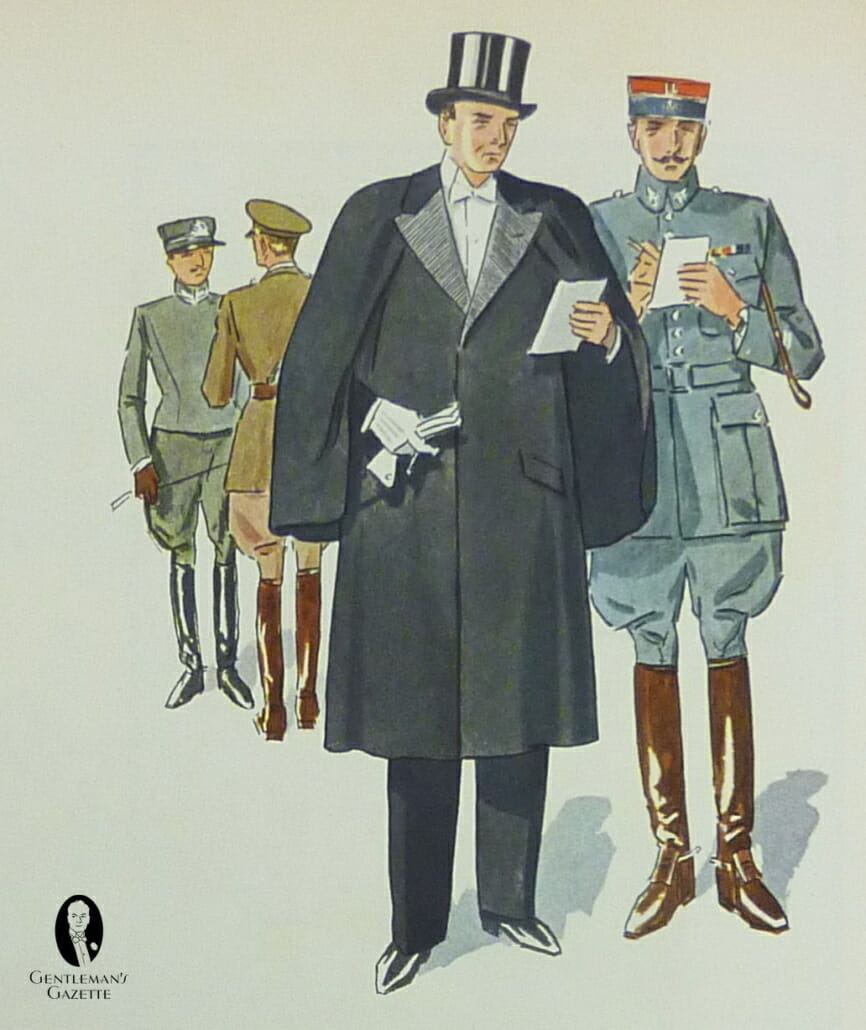

The Top Hat and White Tie

The Early Years

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the chapeau bras was the only hat for evening dress. Also known as a bicorne, it was a crescent-shaped headpiece like the one made famous by Napoleon but was specifically designed as a collapsible hat to be carried under the arm – thus its French name “arm hat”. The tall “round hats” worn as daywear were impractical in comparison because they were awkward to carry at a ball and had to be checked at the opera or theater. That all changed when a collapsible version of the round hat was invented in 1812 which allowed gentlemen to store their headwear under their seats.

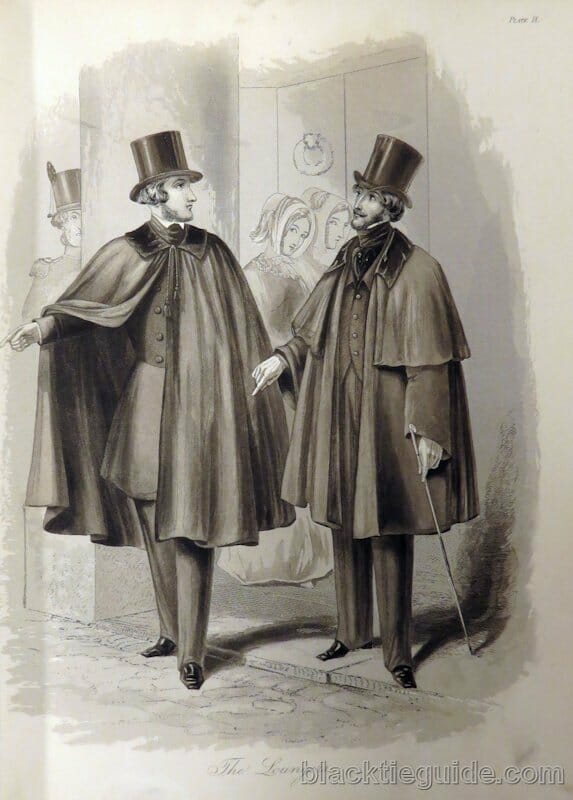

Acceptable at first only for informal evening events, tall hat styles became increasingly popular as full-dress attire in the 1820s with the arrival in England of the French top hat. The standard top hat was made of black silk plush (a pile longer and less dense than velvet pile) or felted beaver fur while early collapsible versions were generally made of the former material.

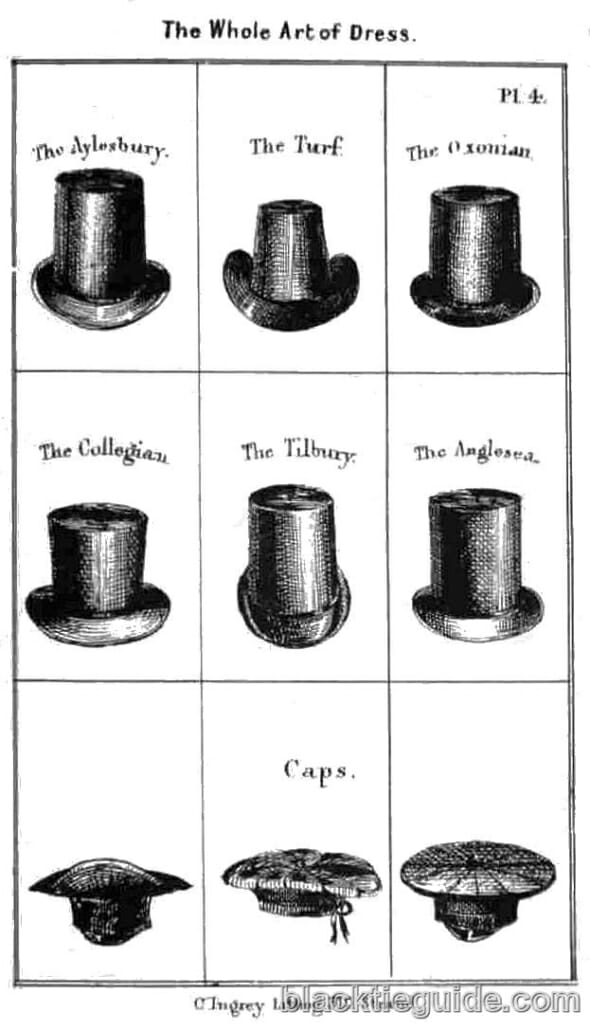

An interesting comparison of silk and beaver fur was offered in the 1830 British etiquette book The Whole Art of Dress. It explained that up to that point beaver was preferred over silk by the nobility and gentry because it was lighter and more pliable thus allowing a wider variety of shapes. However silk hats had recently become available in lighter weights and a variety of shapes and had the advantage of being much more durable than beaver and of retaining their gloss indefinitely while beaver “turns quite brown and looks very shabby”. They were also half the price of beaver.

The Victorian Era

At the dawn of the Victorian era conduct guides such as the American Handbook of the Man of Fashion were still prescribing a chapeau bras for dances or large evening parties because “to carry a common hat on such occasions, as is done by some awkward imitators of fashion, is clumsy and absurd.” Despite this, by the 1840s the top hat “had changed from a fashion novelty to a status symbol for bourgeois men,” explains the McCord Museum’s Web site. “The top hat symbolized respectability, wealth, dignity and social standing: High and imposing, it made men look taller and ‘handsome.” Consequently, when Antoine Gibus perfected the collapsible version of the top hat around 1840 the resulting gibus hat quickly became the most popular headwear after six o’clock.

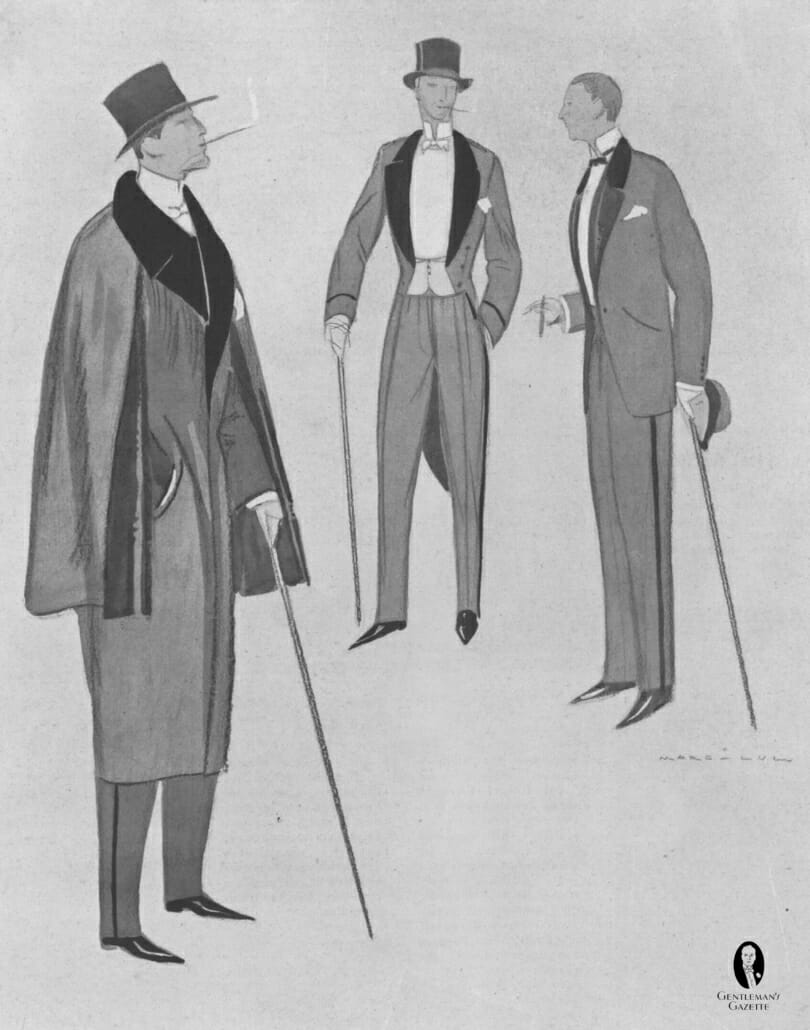

The black top hat remained de rigeur for evening dress throughout the Victorian era with silk models becoming the standard material by the mid-century thanks to their adoption by Prince Albert and the depletion of the North American beaver. The collapsible version of the top hat – which took on the nicknames crush hat and opera hat – also continued to be a common evening option until the Edwardian era when it began to be considered old-fashioned.

The 20th Century

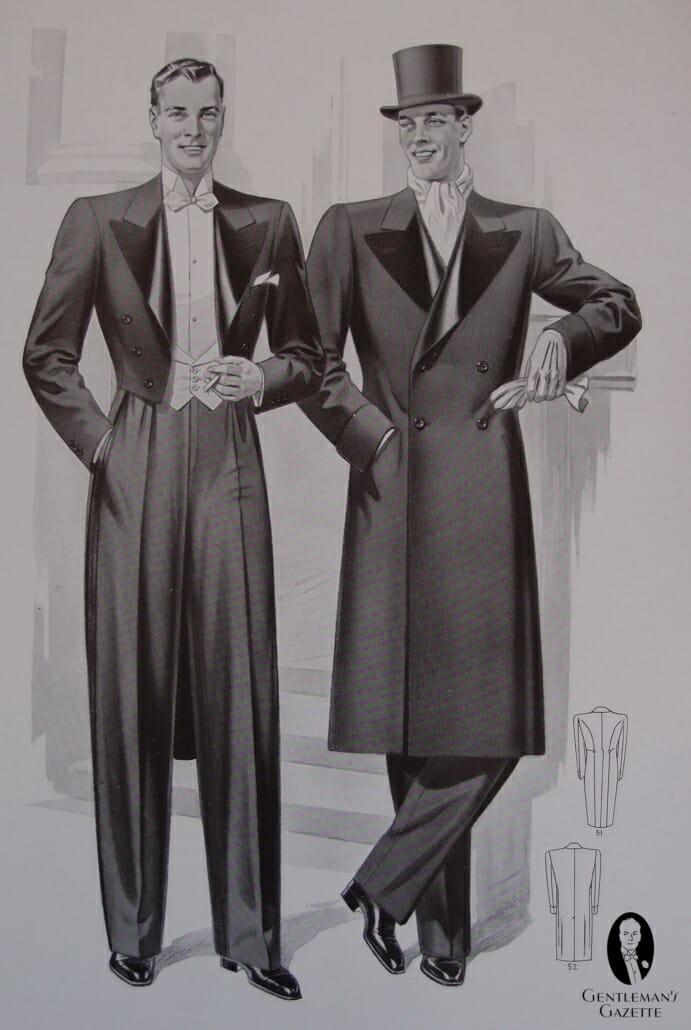

Following World War One the top hat’s tendency to become shoddy after a night at the theater or the ball resulted in a declining popularity until the early 1930s when Apparel Arts reported that the trend was reversing. The periodical also noted the return of the opera hat which in America was now typically made of fine ribbed silk while in England and Europe it was usually constructed of merino cloth.

“If you don’t own a black silk hat or an opera hat don’t wear tails at all.”

1952 Etiquette Manual

Although the Second World War brought about another relaxation of fashion standards, etiquette manuals continued to recommend both the silk hat and opera hat with white tie right through the 1950s with one of them going so far as to say in 1952 that “If you don’t own a black silk hat or an opera hat don’t wear tails at all.” By mid-century though, the black homburg was increasingly accepted as an alternative on both sides of the Atlantic and by the ‘60s going hatless was also a legitimate alternative. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the tables were turned and experts considered any type of hat to be optional instead of imperative.

Black-Tie Hats: 20th Century Innovations

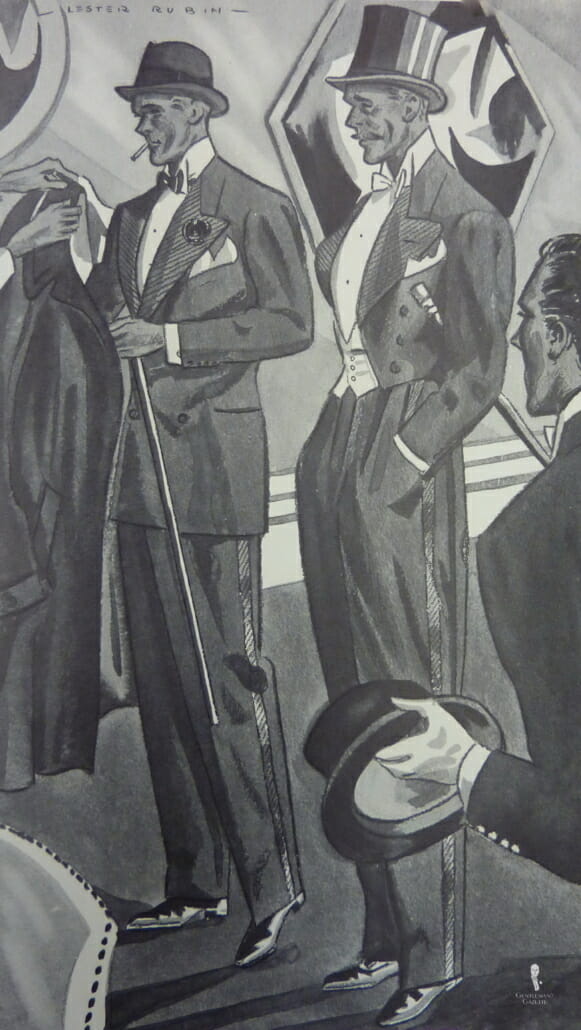

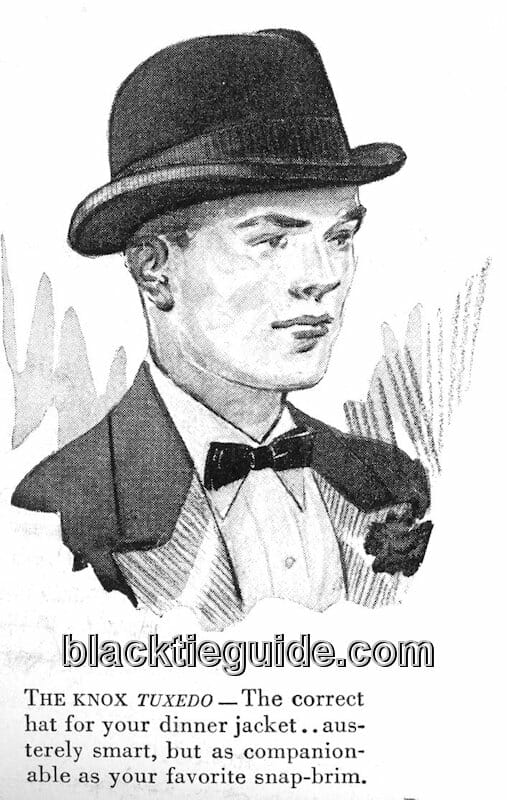

Expert advice regarding black-tie headwear was distinctly schizophrenic at first. In the tuxedo’s early years most etiquette authorities dictated that tall hats were exclusively for long coats and that low hats should be worn with the short dinner jacket. (“Silk is considered bad taste,” said A Dictionary of Men’s Wear in 1908, “opera hat the height of vulgarity.”)

However, there were a significant number of authorities in both the UK and the US that disagreed and specifically prescribed the top hat for all evening wear. Advocates for this position had dwindled significantly by the early 1930s although a few resisted until as late as the 1950s when Emily Post, a longtime stalwart, finally conceded defeat.

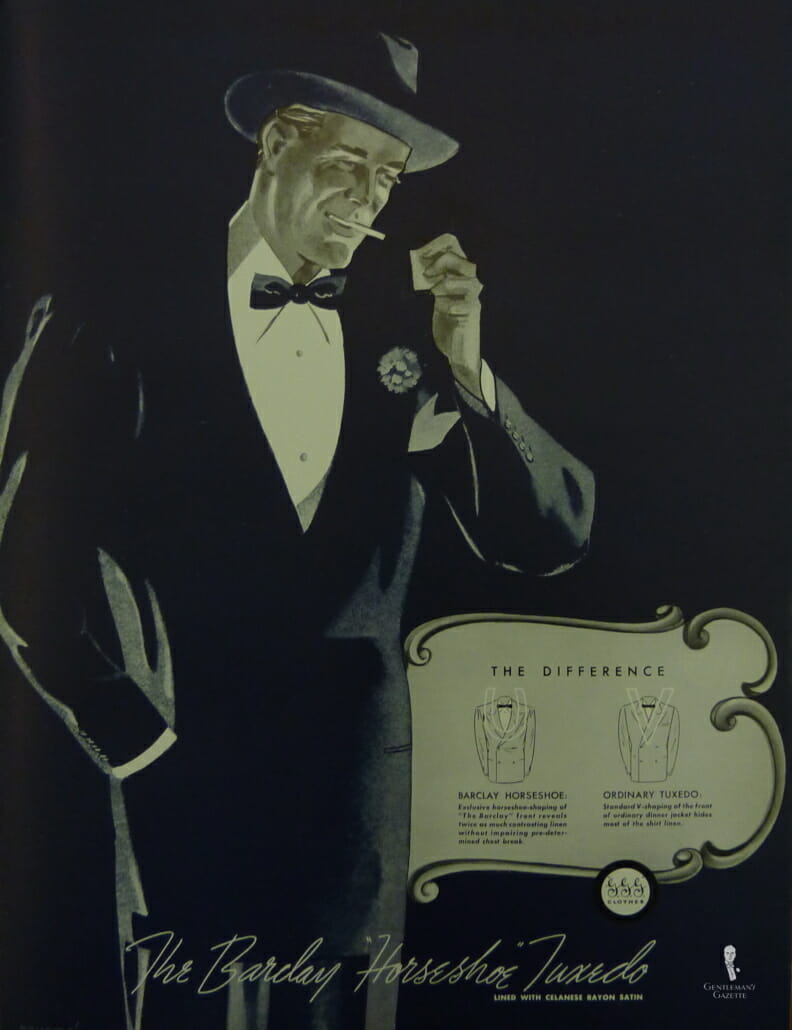

Even amongst the supporters of the low hat there was further disagreement as to which specific styles were appropriate for evening wear. Up until the early 1930s most tended to favor the black stiff derby (sometimes called a bowler in the US) or the black alpine. Others argued soft felt hats such as the alpine or fedora were suitable only for business wear.

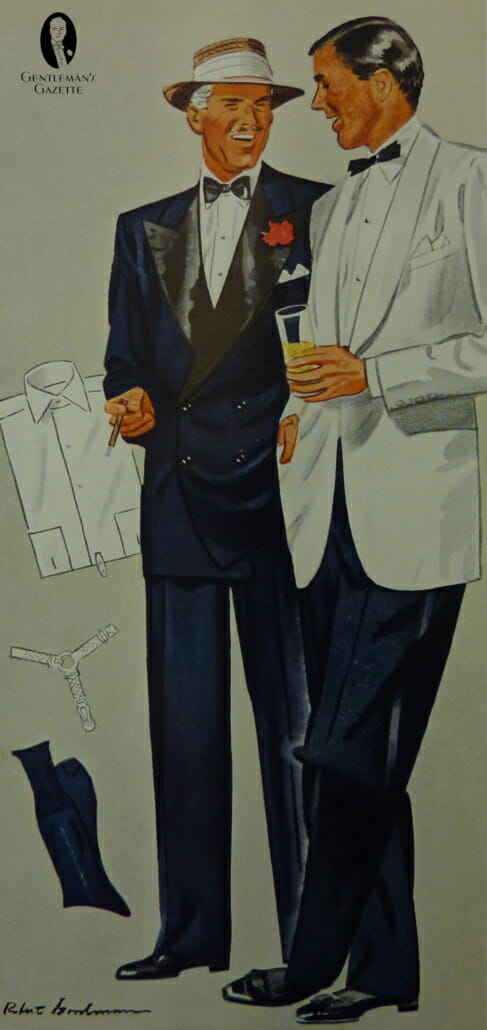

The low hat debate was largely settled with the acceptance of the homburg in the 1930s, a style which combined the stiffness of the top hat and the elegance of the fedora. Whether in black or fashionable midnight blue it remained the preferred black-tie hat up until the 1950s.

By that point the Second World War’s reduction of formality meant soft felt hats were becoming increasingly accepted as an alternative. Finally, just as with white tie, going hatless became an option in the 1960s until the practice grew in popularity to the point where it became the new norm in the 1970s.

Evening Cloaks / Opera Cloaks

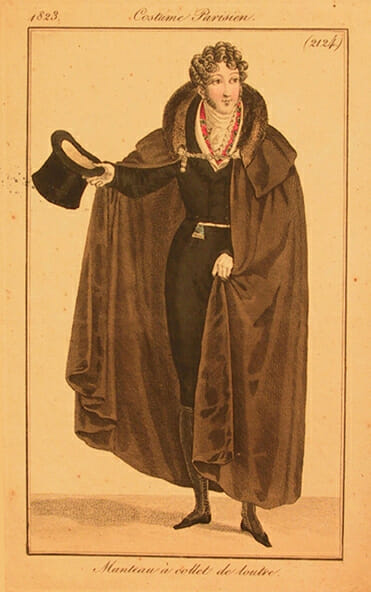

Cloaks were standard outerwear during the English Regency and versions worn with full dress incorporated luxurious linings and trimmings such as colored silk, velvet and fur. They were employed by men and women as a fashion statement or to protect the fine fabrics of their evening wear from the elements, especially where a coat would crush or hide the garments. As they were particularly popular with formal opera-going attire they were often referred to as opera cloaks. These flamboyant vestments began to fall out of fashion in the 1840s with the advent of the more somber Victorian age and the rising popularity of the hybrid Inverness coat that featured a short shoulder cape.

After the mid-nineteenth century, the evening cloak made only sporadic appearances in dress guidelines published by fashion and etiquette authorities. One of the last detailed references can be found in Amy Vanderbilt’s 1952 etiquette book:

Black satin-lined evening cape, an elegant garment, is still seen on gentlemen who take their clothes very seriously and who like to keep alive the niceties of Victorian dress. Usually tailored to measure but sometimes featured by the best men’s shops in lush seasons. Once you own it, you can presumably wear the same cape the rest of your life with complete confidence.

In the late 1950s formal cloaks – by now called “capes” in America – were featured in a few issues of GQ and Esquire despite the fact that the corresponding white-tie rig was rarely seen outside of highly ceremonial occasions. Accordingly, in the late 1960s these same publishers declared the garment was now appropriate with black tie and depicted cloaks with tuxedos on occasion up until the 1990s.

Mufflers and Dress Shirt Protectors

Mufflers

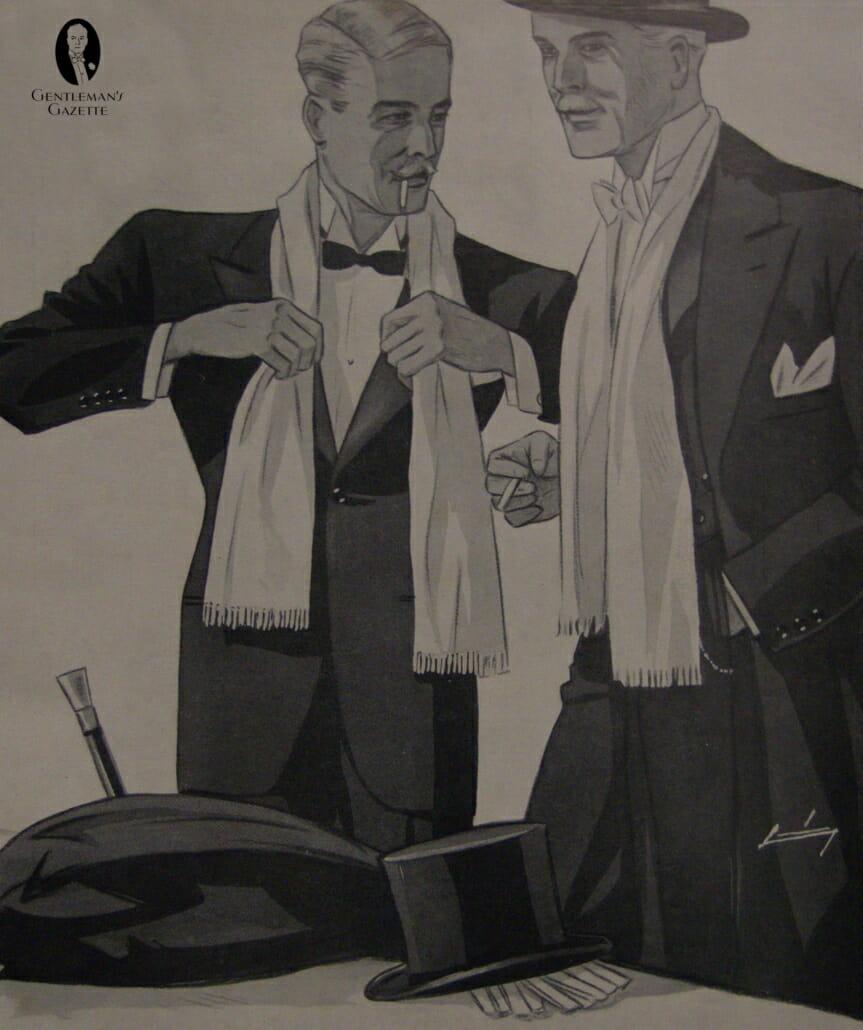

White silk mufflers were recommended for day or evening dress beginning in the 1880s. A 1912 issue of the Sartorial Art Journal provides a very detailed recommendation of what was appropriate with evening wear at that time:

The correct muffler or scarf to go around the neck and chest to protect the waistcoat and shirt is of knitted silk, woven like a knitted tie, black on one side and white on the other, in wear showing as two shades of gray depending on which side is worn outside. About four feet long, 18 inches wide, and has long fringed ends.

Most other turn-of-the-century authorities didn’t mention fringed ends and suggested plain white silk. In fact, wearing white garments was a point of pride owing to the considerable laundering expense required to keep them clean in soot-filled cities of the time. Said one 1894 newspaper report: “The London dandy prides himself as much on the spotless purity and the expanse of his white silk neck scarfs as the dandy of forty years ago did on his many-colored waistcoats.”

Plain white silk remained the norm until modern times with the notable exception of the glory days of menswear in the 1930s. During that period Apparel Arts and Esquireallowed for crepe material, pale yellow color, fringed ends (again) and monogrammed initials. They also recommended wearing the muffler tied in ascot style.

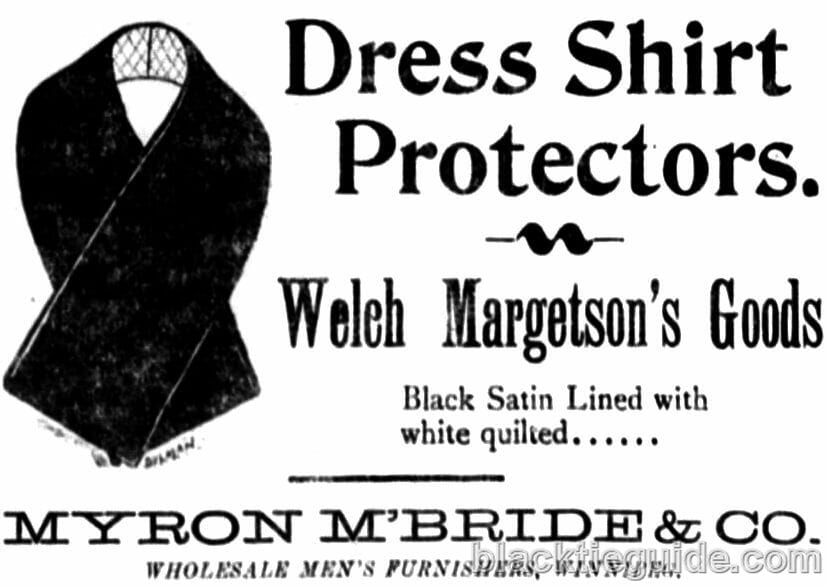

Dress Shirt Protectors

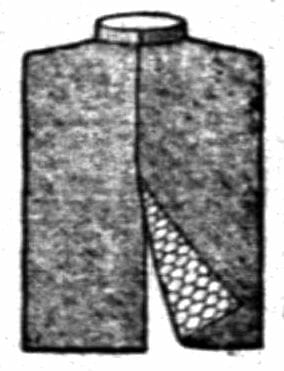

A more effective version of the muffler was the Victorian dress shirt protector. According to History of Underclothes, it was popular in Britain from about 1897 and consisted of “a pad of white quilted satin faced with white silk.”

In the United States, it was more often referred to as a full dress protector and sometimes a dress shirt shield and debuted a decade earlier. Initially made of cotton and wool then of satin or silk, it was essentially an oblong muffler broad enough to cover the expanse of shirt revealed by the open tailcoat front and low-cut evening waistcoat.

It differed from the dress muffler in a couple of ways that made it more practical. Firstly, it was black instead of white owing to its purpose of shielding the snow-white expanse of shirt front from the aforementioned soot that plagued coal-powered cities of the time. Secondly, it was quilted to shield the wearer’s chest from the unhealthy cold. Unlike all other types of men’s suits which buttoned high and/or had a tall waistcoat underneath, the unique design of full dress allowed for only a thin layer of cotton between the wearer and the elements. Concerns of contracting “pneumonia and other diseases” initially prompted the use of the under vest, a sleeveless high-buttoning garment made of warmly lined silk and worn under the shirt. A similar lining was incorporated into the full dress protector thus rendering the undervest unnecessary.

When a collar was added to the protector in 1888 to cover the neck and shirt collar, gentlemen could also do away with their mufflers. A sachet (small package of perfumed powder used to scent clothes) was sometimes added to the protectors although some authorities considered this practice a bit gauche.

In both the UK and the US, dress shirt protectors abruptly fell from popularity at the end of World War One, likely due to the concurrent decline in coal use.

Formal Facts

What’s in a Name? Understanding “Opera”,”Gibus”, and “Claque”

1836 illustration of actual Antoine Gibus top hat

The collapsible top hat is known by numerous names. “Opera hat” refers to the fact it was originally designed to allow tall hats to be stored at the opera or theater without the damage usually inflicted on silk hats. “Gibus hat” refers to Antoine Gibus, the man who perfected the design in the early Victorian period. “Chapeau claque” is based on the noise the hat makes when it is popped open (“claque” is French for “slap”).

What’s in a Name? The Meaning of “Tuxedo Hat”

The term “tuxedo hat” can be found as far back as the 1900s but has no distinct meaning as it was applied to both Fedora and homburg styles, sometimes even by the same authority.

Warm-Weather Hats

Summer hats (and overcoats) are described on the Vintage Warm-Weather Black Tie page.

What’s in a Name? Cloak versus Cape

While both are loose, sleeveless garments that tie around the neck or shoulders, a cloak is longer (usually knee length) and functions like a coat by wrapping the body. A cape is more of a decorative accessory that is shorter (waist length or less) and covers only the wearer’s back. In actual practice, fashion writers often use the terms interchangeably.

What’s in a Name? Muffler versus Scarf versus Reefer

Prior to the 20th century, “scarf” was often used in the context of long neckties (“tie” being reserved specifically for bow ties). Following 1900 the two terms tended to be used interchangeably in the US with scarf becoming preferred after World War II. “Reefer” was often used during this same period to refer to an oblong shape versus the original square version.

Explore this chapter: 8 Vintage Evening Wear

- 8.1 Vintage Black Tie Etiquette & Dress Codes

- 8.2 Vintage Tailcoats & Tuxedos

- 8.3 Vintage Evening Waistcoats & Cummerbunds

- 8.4 Vintage Evening Shirts

- 8.5 Vintage Evening Neckwear

- 8.6 Vintage Evening Footwear

- 8.7 Vintage Evening Accessories

- 8.8 Vintage Evening Outerwear

- 8.9 Vintage Warm-Weather Evening Wear

- 8.10 Vintage Evening Weddings

- 8.11 Retro Evening Wear